When the internet arrived on our desktops in the 1990s, language teachers found themselves able to access huge amounts of authentic texts of all kinds. It was a true game-changer. But when it came to ELT dedicated websites, the pickings were much slimmer. There was a very small number of good ELT resource sites (onestopenglish stood out from the crowd), but more ubiquitous and more enduring were the sites offering downloadable material shared by teachers. One of these, ESLprintables.com, currently has 1,082,522 registered users, compared to the 700,000+ of onestopenglish.

The resources on offer at sites such as these range from texts and scripted dialogues, along with accompanying comprehension questions, to grammar explanations and gapfills, vocabulary matching tasks and gapfills, to lists of prompts for discussions. Almost all of it is unremittingly awful, a terrible waste of the internet’s potential.

Ten years later, interactive online possibilities began to appear. Before long, language teachers found themselves able to use things like blogs, wikis and Google Docs. It was another true game changer. But when it came to ELT dedicated things, the pickings were much slimmer. There is some useful stuff (flashcard apps, for example) out there, but more ubiquitous are interactive versions of the downloadable dross that already existed. Learning platforms, which have such rich possibilities, are mostly loaded with gapfills, drag-and-drop, multiple choice, and so on. Again, it seems such a terrible waste of the technology’s potential. And all of this runs counter to what we know about how people learn another language. It’s as if decades of research into second language acquisition had never taken place.

And now we have AI and large language models like GPT. The possibilities are rich and quite a few people, like Sam Gravell and Svetlana Kandybovich, have already started suggesting interesting and creative ways of using the technology for language teaching. Sadly, though, technology has a tendency to bring out the worst in approaches to language teaching, since there’s always a bandwagon to be jumped on. Welcome to Twee, A.I. powered tools for English teachers, where you can generate your own dross in a matter of seconds. You can generate texts and dialogues, pitched at one of three levels, with or without target vocabulary, and produce comprehension questions (open questions, T / F, or M / C), exercises where vocabulary has to be matched to definitions, word-formation exercises, gapfills. The name of the site has been carefully chosen (Cambridge dictionary defines ‘twee’ as ‘artificially attractive’).

I decided to give it a try. Twee uses the same technology as ChatGPT and the results were unsurprising. I won’t comment in any detail on the intrinsic interest or the accuracy of factual information in the texts. They are what you might expect if you have experimented with ChatGPT. For the same reason, I won’t go into details about the credibility or naturalness of the dialogues. Similarly, the ability of Twee to gauge the appropriacy of texts for particular levels is poor: it hasn’t been trained on a tagged learner corpus. In any case, having only three level bands (A1/A2, B1/B2 and C1/C2) means that levelling is far too approximate. Suffice to say that the comprehension questions, vocabulary-item selection, vocabulary practice activities would all require very heavy editing.

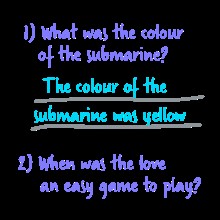

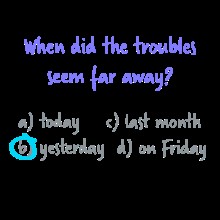

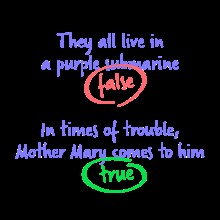

Twee is still in beta, and, no doubt, improvements will come as the large language models on which it draws get bigger and better. Bilingual functionality is a necessary addition, and is doable. More reliable level-matching would be nice, but it’s a huge technological challenge, besides being theoretically problematic. But bigger problems remain and these have nothing to do with technology. Take a look at the examples below of how Twee suggests its reading comprehension tasks (open questions, M / C, T / F) could be used with some Beatles songs.

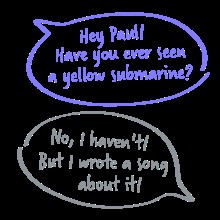

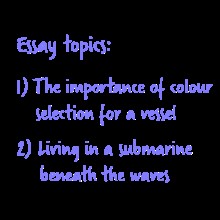

Is there any point getting learners to look at a ‘dialogue’ (on the topic of yellow submarines) like the one below? Is there any point getting learners to write essays using prompts such as those below?

What possible learning value could tasks such as these have? Is there any credible theory of language learning behind any of this, or is it just stuff that would while away some classroom time? AI meets ESLprintables – what a waste of the technology’s potential!

Edtech vendors like to describe their products as ‘solutions’, but the educational challenges, which these products are supposedly solutions to, often remain unexamined. Poor use of technology can exacerbate these challenges by making inappropriate learning materials more easily available.