There’s an aspect of language learning which everyone agrees is terribly important, but no one can quite agree on what to call it. I’m talking about combinations of words, including fixed expressions, collocations, phrasal verbs and idioms. These combinations are relatively fixed, cannot always be predicted from their elements or generated by grammar rules (Laufer, 2022). They are sometimes referred to as formulaic sequences, formulaic expressions, lexical bundles or lexical chunks, among other multiword items. They matter to English language learners because a large part of English consists of such combinations. Hill (2001) suggests this may be up to 70%. More conservative estimates report 58.6% of writing and 52.3% of speech (Erman & Warren, 2000). Some of these combinations (e.g. ‘of course’, ‘at least’) are so common that they fall into lists of the 1000 most frequent lexical items in the language.

By virtue of their ubiquity and frequency, they are important both for comprehension of reading and listening texts and for the speed at which texts can be processed. This is because knowledge of these combinations ‘makes discourse relatively predictable’ (Boers, 2020). Similarly, such knowledge can significantly contribute to spoken fluency because combinations ‘can be retrieved from memory as prefabricated units rather than being assembled at the time of speaking’ (Boer, 2020).

So far, so good, but from here on, the waters get a little muddier. Given their importance, what is the best way for a learner to acquire a decent stock of them? Are they best acquired through incidental learning (through meaning-focused reading and listening) or deliberate learning (e.g. with focused exercises of flashcards)? If the former, how on earth can we help learners to make sure that they get exposure to enough combinations enough times? If the latter, what kind of practice works best and, most importantly, which combinations should be selected? With, at the very least, many tens of thousands of such combinations, life is too short to learn them all in a deliberate fashion. Some sort of triage is necessary, but how should we go about this? Frequency of occurrence would be one obvious criterion, but this merely raises the question of what kind of database should be used to calculate frequency – the spoken discourse of children will reveal very different patterns from the written discourse of, say, applied linguists. On top of that, we cannot avoid consideration of the learners’ reasons for learning the language. If, as is statistically most probable, they are learning English to use as a lingua franca, how important or relevant is it to learn combinations that are frequent, idiomatic and comprehensible in native-speaker cultures, but may be rare and opaque in many English as a Lingua Franca contexts?

There are few, if any, answers to these big questions. Research (e.g. Pellicer-Sánchez, 2020) can give us pointers, but, the bottom line is that we are left with a series of semi-informed options (see O’Keeffe et al., 2007: 58 – 99). So, when an approach comes along that claims to use software to facilitate the learning of English formulaic expressions (Lin, 2022) I am intrigued, to say the least.

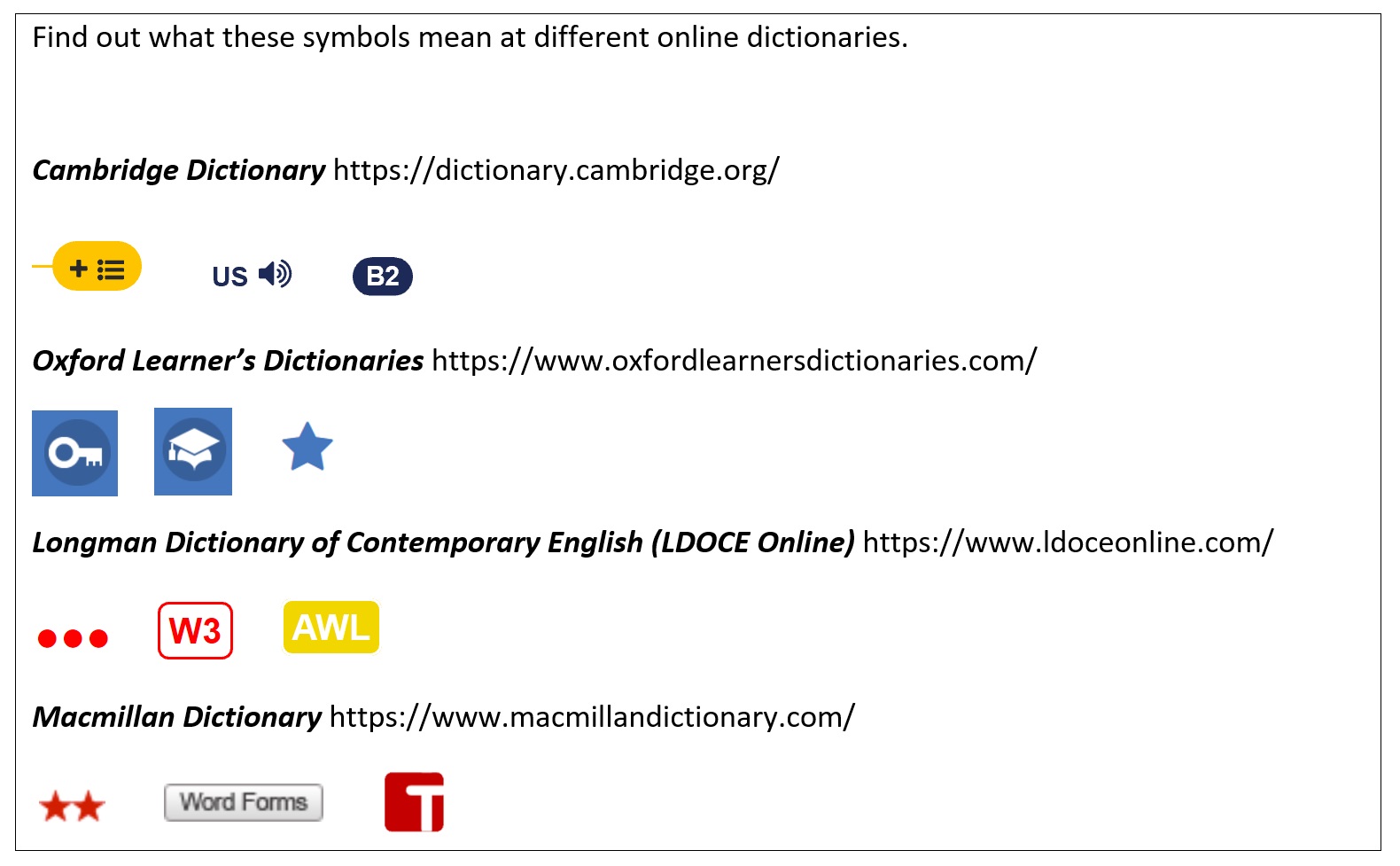

The program is, slightly misleadingly, called IdiomsTube (https://www.idiomstube.com). A more appropriate title would have been IdiomaticityTube (as it focuses on ‘speech formulae, proverbs, sayings, similes, binomials, collocations, and so on’), but I guess ‘idioms’ is a more idiomatic word than ‘idiomaticity’. IdiomsTube allows learners to choose any English-captioned video from YouTube, which is then automatically analysed to identify from two to six formulaic expressions that are presented to the learner as learning objects. Learners are shown these items; the items are hyperlinked to (good) dictionary entries; learners watch the video and are then presented with a small variety of practice tasks. The system recommends particular videos, based on an automated analysis of their difficulty (speech rate and a frequency count of the lexical items they include) and on recommendations from previous users. The system is gamified and, for class use, teachers can track learner progress.

When an article by the program’s developer, Phoebe Lin, (in my view, more of an advertising piece than an academic one) came out in the ReCALL journal, she tweeted that she’d love feedback. I reached out but didn’t hear back. My response here is partly an evaluation of Dr Lin’s program, partly a reflection on how far technology can go in solving some of the knotty problems of language learning.

Incidental and deliberate learning

Researchers have long been interested in looking for ways of making incidental learning of lexical items more likely to happen (Boers, 2021: 39 ff.), of making it more likely that learners will notice lexical items while focusing on the content of a text. Most obviously, texts can be selected, written or modified so they contain multiple instances of a particular item (‘input flooding’). Alternatively, texts can be typographically enhanced so that particular items are highlighted in some way. But these approaches are not possible when learners are given the freedom to select any video from YouTube and when the written presentations are in the form of YouTube captions. Instead, IdiomsTube presents the items before the learner watches the video. They are, in effect, told to watch out for these items in advance. They are also given practice tasks after viewing.

The distinction between incidental and deliberate vocabulary learning is not always crystal-clear. In this case, it seems fairly clear that the approach is more slanted to deliberate learning, even though the selection of video by the learner is determined by a focus on content. Whether this works or not will depend on (1) the level-appropriacy of the videos that the learner watches, (2) the effectiveness of the program in recommending / identifying appropriate videos, (3) the ability of the program to identify appropriate formulaic expressions as learning targets in each video, and (4) the ability of the program to generate appropriate practice of these items.

Evaluating the level of YouTube videos

What makes a video easy or hard to understand? IdiomsTube attempts this analytical task by calculating (1) the speed of the speech and (2) the difficulty of the lexis as determined by the corpus frequency of these items. This gives a score out of five for each category (speed and difficulty). I looked at fifteen videos, all of which were recommended by the program. Most of the ones I looked at were scored at Speed #3 and Difficulty #1. One that I looked at, ‘Bruno Mars Carpool Karaoke’, had a speed of #2 and a difficulty of #1 (i.e. one of the easiest). The video is 15 minutes long. Here’s an extract from the first 90 seconds:

Let’s set this party off right, put yo’ pinky rings up to the moon, twenty four karat magic in the air, head to toe soul player, second verse for the hustlas, gangstas, bad bitches and ya ugly ass friends, I gotta show how a pimp get it in, and they waking up the rocket why you mad

Whoa! Without going into details, it’s clear that something has gone seriously wrong. Evaluating the difficulty of language, especially spoken language, is extremely complex (not least because there’s no objective measure of such a thing). It’s not completely dissimilar to the challenge of evaluating the accuracy, appropriacy and level of sophistication of a learner’s spoken language, and we’re a long way from being able to do that with any acceptable level of reliability. At least, we’re a long, long way from being able to do it well when there are no constraints on the kind of text (which is the case when taking the whole of YouTube as a potential source). Especially if we significantly restrict topic and text type, we can train software to do a much better job. However, this will require human input: it cannot be automated without.

The length of these 15 videos ranged from 3.02 to 29.27 minutes, with the mean length being about 10 minutes, and the median 8.32 minutes. Too damn long.

Selecting appropriate learning items

The automatic identification of formulaic language in a text presents many challenges: it is, as O’Keeffe et al. (2007: 82) note, only partially possible. A starting point is usually a list, and IdiomsTube begins with a list of 53,635 items compiled by the developer (Lin, 2022) over a number of years. The software has to match word combinations in the text to items in the list, and has to recognise variant forms. Formulaic language cannot always be identified just by matching to lists of forms: a piece of cake may just be a piece of cake, and therefore not a piece of cake to analyse. 53,365 items may sound like a lot, but a common estimate of the number of idioms in English is 25,000. The number of multiword units is much, much higher. 53,365 is not going to be enough for any reliable capture.

Since any given text is likely to contain a lot of formulaic language, the next task is to decide how to select for presentation (i.e. as learning objects) from those identified. The challenge is, as Lin (2022) remarks, both technical and theoretical: how can frequency and learnability be measured? There are no easy answers, and the approach of IdiomsTube is, by its own admission, crude. The algorithm prioritises longer items that contain lower frequency single items, and which have a low frequency of occurrence in a corpus of 40,000 randomly-sampled YouTube videos. The aim is to focus on formulaic language that is ‘more challenging in terms of composition (i.e. longer and made up of more difficult words) and, therefore, may be easier to miss due to their infrequent appearance on YouTube’. My immediate reaction is to question whether this approach will not prioritise items that are not worth the bother of deliberate learning in the first place.

The proof is in the proverbial pudding, so I looked at the learning items that were offered by my sample of 15 recommended videos. Sadly, IdiomsTube does not even begin to cut the mustard. The rest of this section details why the selection was so unsatisfactory: you may want to skip this and rejoin me at the start of the next section.

- In total 85 target items were suggested. Of these 39 (just under half) were not fixed expressions. They were single items. Some of these single items (e.g. ‘blog’ and ‘password’ would be extremely easy for most learners). Of the others, 5 were opaque idioms (the most prototypical kind of idiom), the rest were collocations and fixed (but transparent) phrases and frames.

- Some items (e.g. ‘I rest my case’) are limited in terms of the contexts in which they can be appropriately used.

- Some items did not appear to be idiomatic in any way. ‘We need to talk’ and ‘able to do it’, for example, are strange selections, compared to others in their respective lists. They are also very ‘easy’: if you don’t readily understand items like these, you wouldn’t have a hope in hell of understanding the video.

- There were a number of errors in the recommended target items. Errors included duplication of items within one set (‘get in the way’ + ‘get in the way of something’), misreading of an item (‘the shortest’ misread as ‘the shorts’), mislabelling of an item (‘vend’ instead of ‘vending machine’), linking to the wrong dictionary entry (e.g. ‘mini’ links to ‘miniskirt’, although in the video ‘mini’ = ‘small’, or, in another video, ‘stoke’ links to ‘stoked’, which is rather different!).

- The selection of fixed expressions is sometimes very odd. In one video, the following items have been selected: get into an argument, vend, from the ground up, shovel, we need to talk, prefecture. The video contains others which would seem to be better candidates, including ‘You can’t tell’ (which appears twice), ‘in charge of’, ‘way too’ (which also appears twice), and ‘by the way’. It would seem, therefore, that some inappropriate items are selected, whilst other more appropriate ones are omitted.

- There is a wide variation in the kind of target item. One set, for example, included: in order to do, friction, upcoming, run out of steam, able to do it, notification. Cross-checking with Pearson’s Global Scale of English, we have items ranging from A2 to C2+.

The challenges of automation

IdiomsTube comes unstuck on many levels. It fails to recommend appropriate videos to watch. It fails to suggest appropriate language to learn. It fails to provide appropriate practice. You wouldn’t know this from reading the article by Phoebe Lin in the ReCALL journal which does, however, suggest that ‘further improvements in the design and functions of IdiomsTube are needed’. Necessary they certainly are, but the interesting question is how possible they are.

My interest in IdiomsTube comes from my own experience in an app project which attempted to do something not completely dissimilar. We wanted to be able to evaluate the idiomaticity of learner-generated language, and this entailed identifying formulaic patterns in a large corpus. We wanted to develop a recommendation engine for learning objects (i.e. the lexical items) by combining measures of frequency and learnability. We wanted to generate tasks to practise collocational patterns, by trawling the corpus for contexts that lent themselves to gapfills. With some of these challenges, we failed. With others, we found a stopgap solution in human curation, writing and editing.

IdiomsTube is interesting, not because of what it tells us about how technology can facilitate language learning. It’s interesting because it tells us about the limits of technological applications to learning, and about the importance of sorting out theoretical challenges before the technical ones. It’s interesting as a case study is how not to go about developing an app: its ‘special enhancement features such as gamification, idiom-of-the-day posts, the IdiomsTube Teacher’s interface and IdiomsTube Facebook and Instagram pages’ are pointless distractions when the key questions have not been resolved. It’s interesting as a case study of something that should not have been published in an academic journal. It’s interesting as a case study of how techno-enthusiasm can blind you to the possibility that some learning challenges do not have solutions that can be automated.

References

Boers, F. (2020) Factors affecting the learning of multiword items. In Webb, S. (Ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Vocabulary Studies. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 143 – 157

Boers, F. (2021) Evaluating Second Language Vocabulary and Grammar Instruction. Abingdon: Routledge

Erman, B. & Warren, B. (2000) The idiom principle and the open choice principle. Text, 20 (1): pp. 29 – 62

Hill, J. (2001) Revising priorities: from grammatical failure to collocational success. In Lewis, M. (Ed.) Teaching Collocation: further development in the Lexical Approach. Hove: LTP. Pp.47- 69

Laufer, B. (2022) Formulaic sequences and second language learning. In Szudarski, P. & Barclay, S. (Eds.) Vocabulary Theory, Patterning and Teaching. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. pp. 89 – 98

Lin, P. (2022). Developing an intelligent tool for computer-assisted formulaic language learning from YouTube videos. ReCALL 34 (2): pp.185–200.

O’Keeffe, A., McCarthy, M. & Carter, R. (2007) From Corpus to Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Pellicer-Sánchez, A. (2020) Learning single words vs. multiword items. In Webb, S. (Ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Vocabulary Studies. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 158 – 173

As both a language learner and a teacher, I have a number of questions about the value of watching subtitled videos for language learning. My interest is in watching extended videos, rather than short clips for classroom use, so I am concerned with incidental, rather than intentional, learning, mostly of vocabulary. My questions include:

As both a language learner and a teacher, I have a number of questions about the value of watching subtitled videos for language learning. My interest is in watching extended videos, rather than short clips for classroom use, so I am concerned with incidental, rather than intentional, learning, mostly of vocabulary. My questions include: