My attention was recently drawn (thanks to Grzegorz Śpiewak) to a recent free publication from OUP. It’s called ‘Multimodality in ELT: Communication skills for today’s generation’ (Donaghy et al., 2023) and it’s what OUP likes to call a ‘position paper’: it offers ‘evidence-based recommendations to support educators and learners in their future success’. Its topic is multimodal (or multimedia) literacy, a term used to describe the importance for learners of being able ‘not just to understand but to create multimedia messages, integrating text with images, sounds and video to suit a variety of communicative purposes and reach a range of target audiences’ (Dudeney et al., 2013: 13).

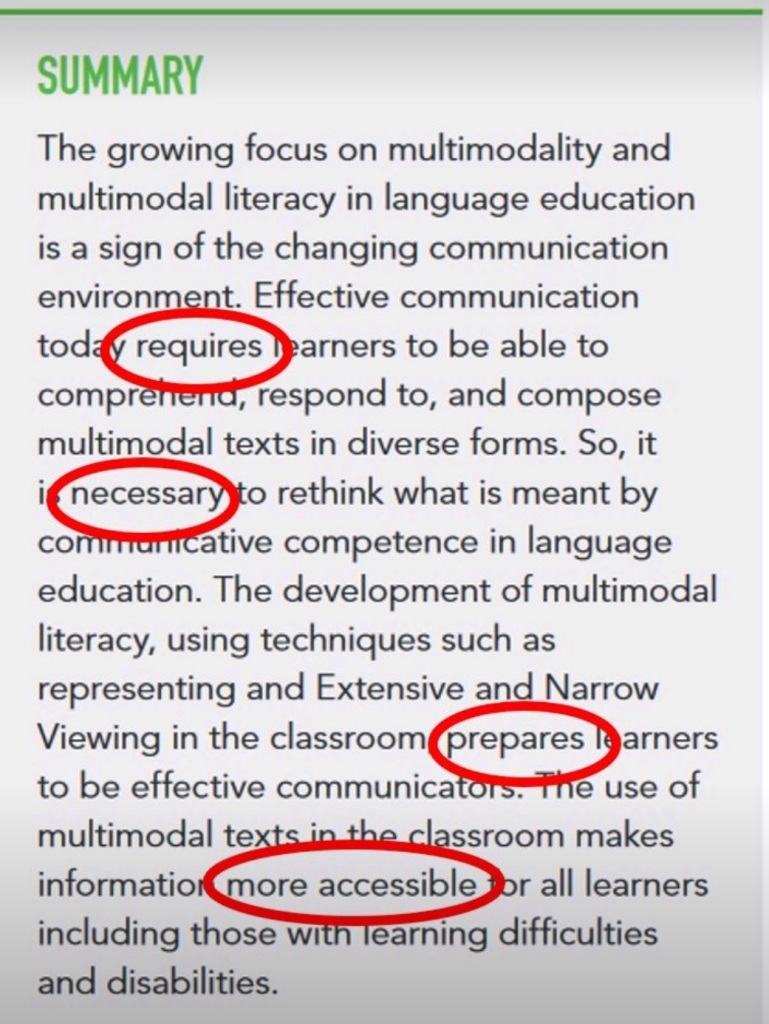

Grzegorz noted the author of this paper’s ‘positively charged, unhedged language to describe what is arguably a most complex problem area’. As an example, he takes the summary of the first section and circles questionable and / or unsubstantiated claims. It’s just one example from a text that reads more like a ‘manifesto’ than a balanced piece of evidence-reporting. The verb ‘need’ (in the sense of ‘must’, as in ‘teachers / learners / students need to …’) appears no less than 57 times. The modal ‘should’ (as in ‘teachers / learners / students should …’) clocks up 27 appearances.

What is it then that we all need to do? Essentially, the argument is that English language teachers need to develop their students’ multimodal literacy by incorporating more multimodal texts and tasks (videos and images) in all their lessons. The main reason for this appears to be that, in today’s digital age, communication is more often multimodal than not (i.e. monomodal written or spoken text). As an addendum, we are told that multimodal classroom practices are a ‘fundamental part of inclusive teaching’ in classes with ‘learners with learning difficulties and disabilities’. In case you thought it was ironic that such an argument would be put forward in a flat monomodal pdf, OUP also offers the same content through a multimodal ‘course’ with text, video and interactive tasks.

It might all be pretty persuasive, if it weren’t so overstated. Here are a few of the complex problem areas.

What exactly is multimodal literacy?

We are told in the paper that there are five modes of communication: linguistic, visual, aural, gestural and spatial. Multimodal literacy consists, apparently, of the ability

- to ‘view’ multimodal texts (noticing the different modes, and, for basic literacy, responding to the text on an emotional level, and, for more advanced literacy, respond to it critically)

- to ‘represent’ ideas and information in a multimodal way (posters, storyboards, memes, etc.)

I find this frustratingly imprecise. First: ‘viewing’. Noticing modes and reacting emotionally to a multimedia artefact do not take anyone very far on the path towards multimodal literacy, even if they are necessary first steps. It is only when we move towards a critical response (understanding the relative significance of different modes and problematizing our initial emotional response) that we can really talk about literacy (see the ‘critical literacy’ of Pegrum et al., 2018). We’re basically talking about critical thinking, a concept as vague and contested as any out there. Responding to a multimedia artefact ‘critically’ can mean more or less anything and everything.

Next: ‘representing’. What is the relative importance of ‘viewing’ and ‘representing’? What kinds of representations (artefacts) are important, and which are not? Presumably, they are not all of equal importance. And, whichever artefact is chosen as the focus, a whole range of technical skills will be needed to produce the artefact in question. So, precisely what kind of representing are we talking about?

Priorities in the ELT classroom

The Oxford authors write that ‘the main focus as English language teachers should obviously be on language’. I take this to mean that the ‘linguistic mode’ of communication should be our priority. This seems reasonable, since it’s hard to imagine any kind of digital literacy without some reading skills preceding it. But, again, the question of relative importance rears its ugly head. The time available for language leaning and teaching is always limited. Time that is devoted to the visual, aural, gestural or spatial modes of communication is time that is not devoted to the linguistic mode.

There are, too, presumably, some language teaching contexts (I’m thinking in particular about some adult, professional contexts) where the teaching of multimodal literacy would be completely inappropriate.

Multimodal literacy is a form of digital literacy. Writers about digital literacies like to say things like ‘digital literacies are as important to language learning as […] reading and writing skills’ or it is ‘crucial for language teaching to […] encompass the digital literacies which are increasingly central to learners’ […] lives’ (Pegrum et al, 2022). The question then arises: how important, in relative terms, are the various digital literacies? Where does multimodal literacy stand?

The Oxford authors summarise their view as follows:

There is a need for a greater presence of images, videos, and other multimodal texts in ELT coursebooks and a greater focus on using them as a starting point for analysis, evaluation, debate, and discussion.

My question to them is: greater than what? Typical contemporary courseware is already a whizzbang multimodal jamboree. There seem to me to be more pressing concerns with most courseware than supplementing it with visuals or clickables.

Evidence

The Oxford authors’ main interest is unquestionably in the use of video. They recommend extensive video viewing outside the classroom and digital story-telling activities inside. I’m fine with that, so long as classroom time isn’t wasted on getting to grips with a particular digital tool (e.g. a video editor, which, a year from now, will have been replaced by another video editor).

I’m fine with this because it involves learners doing meaningful things with language, and there is ample evidence to indicate that a good way to acquire language is to do meaningful things with it. However, I am less than convinced by the authors’ claim that such activities will strengthen ‘active and critical viewing, and effective and creative representing’. My scepticism derives firstly from my unease about the vagueness of the terms ‘viewing’ and ‘representing’, but I have bigger reservations.

There is much debate about the extent to which general critical thinking can be taught. General critical viewing has the same problems. I can apply critical viewing skills to some topics, because I have reasonable domain knowledge. In my case, it’s domain knowledge that activates my critical awareness of rhetorical devices, layout, choice of images and pull-out quotes, multimodal add-ons and so on. But without the domain knowledge, my critical viewing skills are likely to remain uncritical.

Perhaps most importantly of all, there is a lack of reliable research about ‘the extent to which language instructors should prioritize multimodality in the classroom’ (Kessler, 2022: 552). There are those, like the authors of this paper, who advocate for a ‘strong version’ of multimodality. Others go for a ‘weak version’ ‘in which non-linguistic modes should only minimally support or supplement linguistic instruction’ (Kessler, 2022: 552). And there are others who argue that multimodal activities may actually detract from or stifle L2 development (e.g. Manchón, 2017). In the circumstances, all the talk of ‘needs to’ and ‘should’ is more than a little premature.

Assessment

The authors of this Oxford paper rightly note that, if we are to adopt a multimodal approach, ‘it is important that assessment requirements take into account the multimodal nature of contemporary communication’. The trouble is that there are no widely used assessments (to my knowledge) that do this (including Oxford’s own tests). English language reading tests (like the Oxford Test of English) measure the comprehension of flat printed texts, as a proxy for reading skills. This is not the place to question the validity of such reading tests. Suffice to say that ‘little consensus exists as to what [the ability to read another language] entails, how it develops, and how progress in development can be monitored and fostered’ (Koda, 2021).

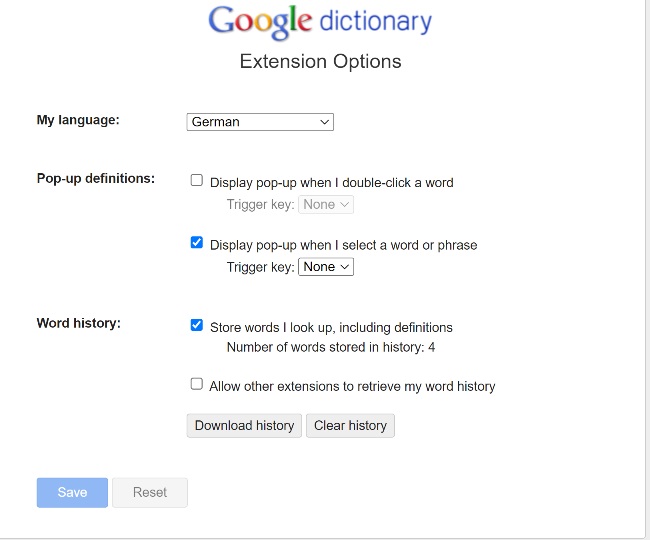

No doubt there are many people beavering away at trying to figure out how to assess multimodal literacy, but the challenges they face are not negligible. Twenty-first century digital (multimodal) literacy includes such things as knowing how to change the language of an online text to your own (and vice versa), how to bring up subtitles, how to convert written text to speech, how to generate audio scripts. All such skills may well be very valuable in this digital age, and all of them limit the need to learn another language.

Final thoughts

I can’t help but wonder why Oxford University Press should bring out a ‘position paper’ that is so at odds with their own publishing and assessing practices, and so at odds with the paper recently published in their flagship journal, ELT Journal. There must be some serious disconnect between the Marketing Department, which commissions papers such as these, and other departments within the company. Why did they allow such overstatement, when it is well known that many ELT practitioners (i.e. their customers) have the view that ‘linguistically based forms are (and should be) the only legitimate form of literacy’ (Choi & Yi, 2016)? Was it, perhaps, the second part of the title of this paper that appealed to the marketing people (‘Communication Skills for Today’s Generation’) and they just thought that ‘multimodality’ had a cool, contemporary ring to it? Or does the use of ‘multimodality’ help the marketing of courses like Headway and English File with additional multimedia bells and whistles? As I say, I can’t help but wonder.

If you want to find out more, I’d recommend the ELT Journal article, which you can access freely without giving your details to the marketing people.

Finally, it is perhaps time to question the logical connection between the fact that much reading these days is multimodal and the idea that multimodal literacy should be taught in a language classroom. Much reading that takes place online, especially with multimodal texts, could be called ‘hyper reading’, characterised as ‘sort of a brew of skimming and scanning on steroids’ (Baron, 2021: 12). Is this the kind of reading that should be promoted with language learners? Baron (2021) argues that the answer to this question depends on the level of reading skills of the learner. The lower the level, the less beneficial it is likely to be. But for ‘accomplished readers with high levels of prior knowledge about the topic’, hyper-reading may be a valuable approach. For many language learners, monomodal deep reading, which demands ‘slower, time-demanding cognitive and reflective functions’ (Baron, 2021: x – xi) may well be much more conducive to learning.

References

Baron, N. S. (2021) How We Read Now. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Choi, J. & Yi, Y. (2016) Teachers’ Integration of Multimodality into Classroom Practices for English Language Learners’ TESOL Journal, 7 (2): 3-4 – 327

Donaghy, K. (author), Karastathi, S. (consultant), Peachey, N. (consultant), (2023). Multimodality in ELT: Communication skills for today’s generation [PDF]. Oxford University Press. https://elt.oup.com/feature/global/expert/multimodality (registration needed)

Dudeney, G., Hockly, N. & Pegrum, M. (2013) Digital Literacies. Harlow: Pearson Education

Kessler, M. (2022) Multimodality. ELT Journal, 76 (4): 551 – 554

Koda, K. (2021) Assessment of Reading. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0051.pub2

Manchón, R. M. (2017) The Potential Impact of Multimodal Composition on Language Learning. Journal of Second Language Writing, 38: 94 – 95

Pegrum, M., Dudeney, G. & Hockly, N. (2018) Digital Literacies Revisited. The European Journal of Applied Linguistics and TEFL, 7 (2): 3 – 24

Pegrum, M., Hockly, N. & Dudeney, G. (2022) Digital Literacies 2nd Edition. New York: Routledge