I must begin by apologizing for my last, flippant blog post where I spun a tale about using generative AI to produce ‘teacher development content’ and getting rid of teacher trainers. I had just watched a webinar by Giuseppe Tomasello of edugo.ai, ‘Harnessing Generative AI to Supercharge Language Education’, and it felt as if much of the script of this webinar had been generated by ChatGPT: ‘write a relentlessly positive product pitch for a language teaching platform in the style of a typical edtech vendor’.

In the webinar, Tomasello talked about using GPT-3 to generate texts for language learners. Yes, it’s doable, the results are factually and linguistically accurate, but dull in the extreme (see Steve Smith’s experiment with some texts for French learners). André Hedlund summarises: ‘limited by a rigid structure … no big differences in style or linguistic devices. They follow a recipe, a formula.’ Much like many coursebook / courseware texts, in other words.

More interesting texts can be generated with GPT-3 when the prompts are crafted in careful detail, but this requires creative human imagination. Crafting such prompts requires practice, trial and error, and it requires knowledge of the intended readers.

AI can be used to generate dull texts at a certain level (B1, B2, C1, etc.), but reliability is a problem. So many variables (starting with familiarity with the subject matter and the learner’s first language) impact on levels of reading difficulty that automation can never satisfactorily resolve this challenge.

However, the interesting question is not whether we can quickly generate courseware-like texts using GPT-3, but whether we should even want to. What is the point of using such texts? Giuseppe Tomasello’s demonstration made it clear that the way these texts should be exploited is by using (automatically generating) a series of comprehension questions and a list of key words which can also be (automatically) converted into a variety of practice tasks (flashcards, gapfills, etc.). Like courseware texts, then, these texts are language objects (TALOs), to be tested for comprehension and mined for items to be deliberately learnt. They are not, in any meaningful way, texts as vehicles of information (TAVIs) – see here for more about TALOs and TAVIs.

Comprehension testing is a standard feature of language teaching, but there are good reasons to believe that it will do little, if anything, to improve a learner’s reading skills (see, for example, Swan & Walter, 2017; Grabe, W. & Yamashita, J., 2022) or language competence. It has nothing to do with the kind of extensive reading (see, for example, Leather & Uden, 2021) that is known to be such a powerful force in language acquisition. This use of text is all about deliberate language study. We are talking here about a synthetic approach to language learning.

The problem, of course, is that deliberate language study is far from uncontested. Synthetic approaches wrongly assume that ‘the explicit teaching of declarative knowledge (knowledge about the L2) will lead to the procedural knowledge learners need in order to successfully use the L2 for communicative purpose’ (see Geoff Jordan on this topic). Even if it were true that some explicit teaching was of value, it’s widely agreed that explicit teaching should not form the core of a language learning syllabus. The edugo.ai product, however, is basically all about explicit teaching.

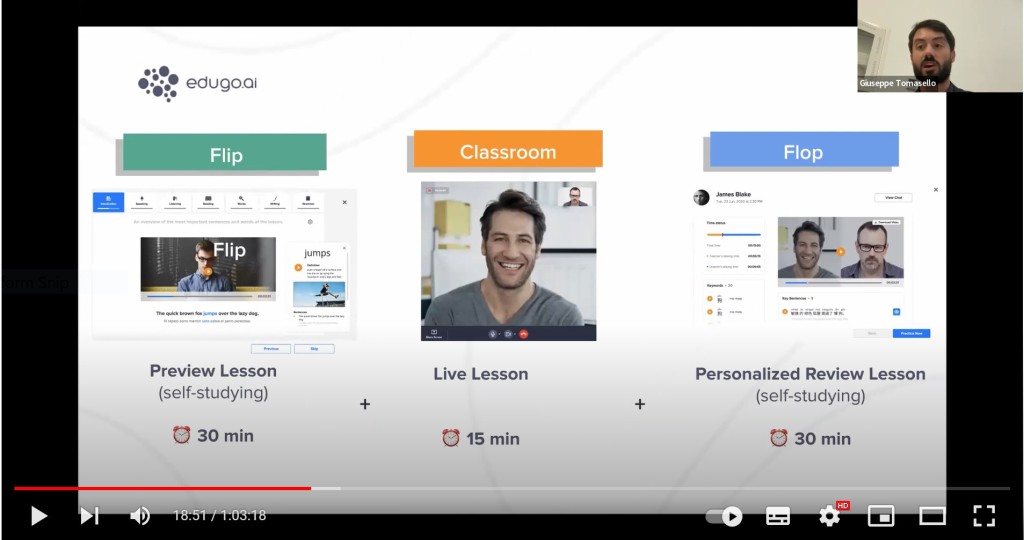

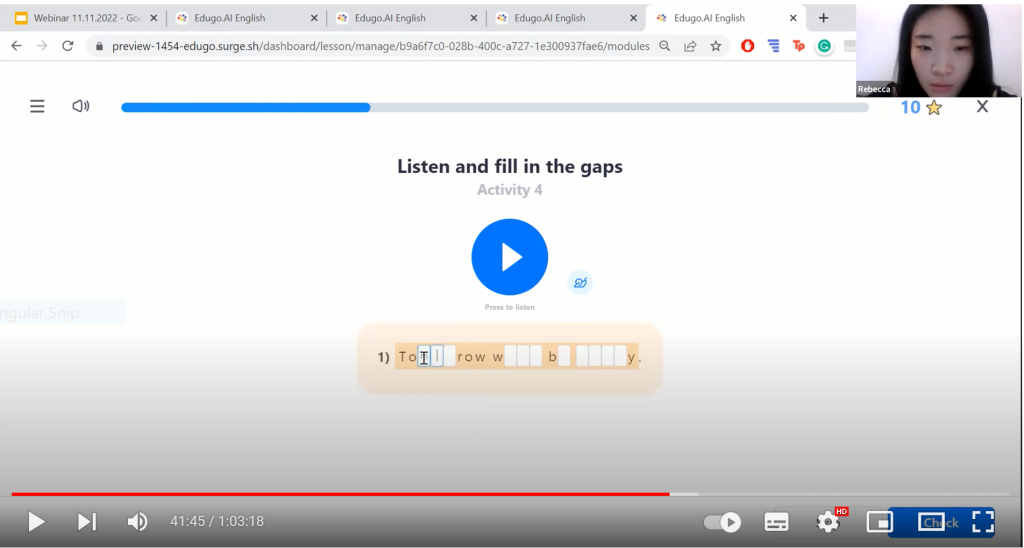

Judging from the edugo.ai presentation on YouTube, the platform offers a wide range of true / false, multiple choice questions, gapfills, dictations and so on, all of which can be gamified. The ‘methodology’ is called ‘Flip and Flop the Classroom’. In this approach, learners do some self-study (presumably of some pre-selected discrete language item(s), practise it in the synchronous lesson, and then have more self-study where this language is reviewed. In the ‘flop’ section, the learner’s spoken contribution to the live lesson is recorded, transcribed and analysed by the system which identifies aspects of the learner’s language which can be improved through personalized practice.

The focus is squarely on accuracy, and the importance of accuracy is underlined by the presenter’s observation that Communicative Language Teaching does not focus enough on accuracy. Accuracy is also to the fore in another task type, strangely called ‘chunking’ (see below). Apparently, this will lead to fluency: ‘The goal of this template is that they can repeat it a lot of times and reach fluency at the end’.

The YouTube presentation is called ‘How to structure your language course using popular pedagogical approaches’ and suggests that you can mix’n’match bits from ‘Grammar Translation’, ‘Direct Method’ and ‘CLT’. Sorry, Giuseppe, you can mix’n’match all you like, but you can’t be methodologically agnostic. This is a synthetic approach all the way down the line. As such, it’s not going to supercharge language education. It’s basically more of what we already have too much of.

Let’s assume, though, for a moment that what we really want is a kind of supercharged, personalizable, quickly generated combination of vocabulary flashcards and ‘English Grammar in Use’ loaded with TALOs. How does this product stand up? We’ll need to consider two related questions: (1) its reliability, and (2) how time-saving it actually is.

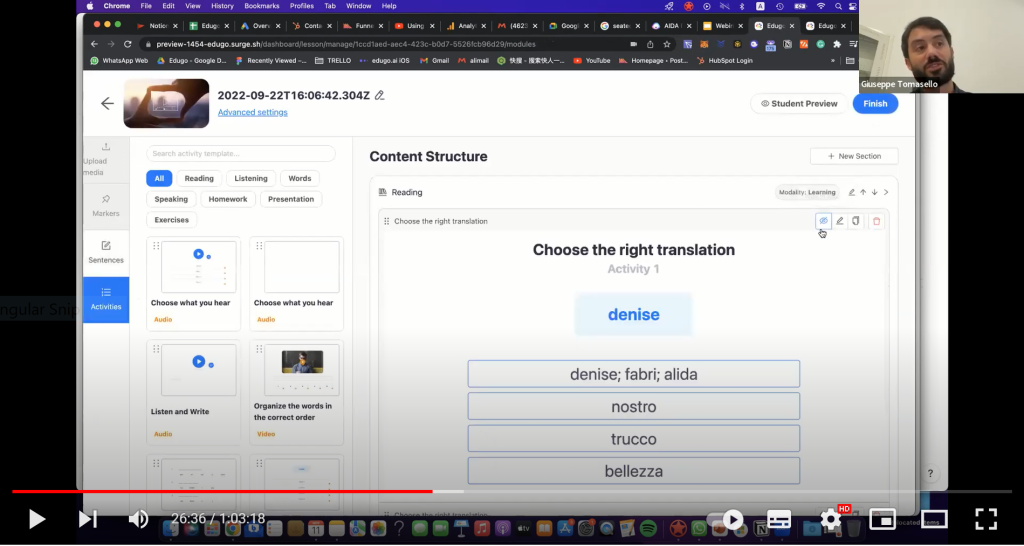

As far as I can judge from the YouTube presentation, reliability is not exactly optimal. There’s the automated key word identifier that identified ‘Denise’, ‘the’ and ‘we’ as ‘key words’ in an extract of learner-produced text (‘Hello, my name is Denise and I founded my makeup company in 2021. We produce skin care products using 100% natural ingredients.’). There’s the automated multiple choice / translation generator which tests your understanding of ‘Denise’ (see below), and there’s the voice recognition software which transcribed ‘it cost’ as ‘they cost’.

In the more recent ‘webinar’ (i.e commercial presentation) that has not yet been uploaded to YouTube, participants identified a number of other bloopers. In short, reliability is an issue. This shouldn’t surprise anyone. Automation of some of these tasks is extremely difficult (see my post about the automated generation of vocabulary learning materials). Perhaps impossible … but how much error is acceptable?

edugo.ai does not sell content: they sell a platform for content-generation, course-creation and selling. Putative clients are institutions wanting to produce and sell learning content of the synthetic kind. The problem with a lack of reliability, any lack of reliability, is that you immediately need skilled staff to work with the platform, to check for error, to edit, to improve on the inevitable limitations of the AI (starting, perhaps, with the dull texts it has generated). It is disingenuous to suggest that anyone can do this without substantial training / supervision. Generative AI only offers a time-saving route, which does not sacrifice reliability, if a skilled and experienced writer is working with it.

edugo.ai is a young start-up that raised $345K in first round funding in September of last year. The various technologies they are using are expensive, and a lot more funding will be needed to make the improvements and additions (such as spaced repetition) that are necessary. In both presentations, there was lots of talk that the platform will be able to do this and will be able to do that. For the moment, though, nothing has been proved, and my suspicion is that some of the problems they are trying to solve do not have technological solutions. First of all, they’ll need a better understanding of what these problems are, and, for that, there has to be a coherent and credible theory of second language acquisition. There are all sorts of good uses that GPT-3 / AI could be put to in language teaching. I doubt this is one of them.

To wrap up, here’s a little question. What are the chances that edugo.ai’s claims that the product will lead to ‘+50% student engagement’ and ‘5X Faster creating language courses’ were also generated by GPT-3?

References

Grabe, W. & Yamashita, J. (2022) Reading in a Second Language 2nd edition. New York: Cambridge University Press

Leather, S. & Uden, J. (2021) Extensive Reading. New York: Routledge

Swan, M. & Walter, C. (2017) Misunderstanding comprehension. ELT Journal, 71 (2): 228 – 236

My first question was: how do conference presenters feel about personalised learning? One way of finding out is by looking at the adjectives that are found in close proximity. This is what you get.

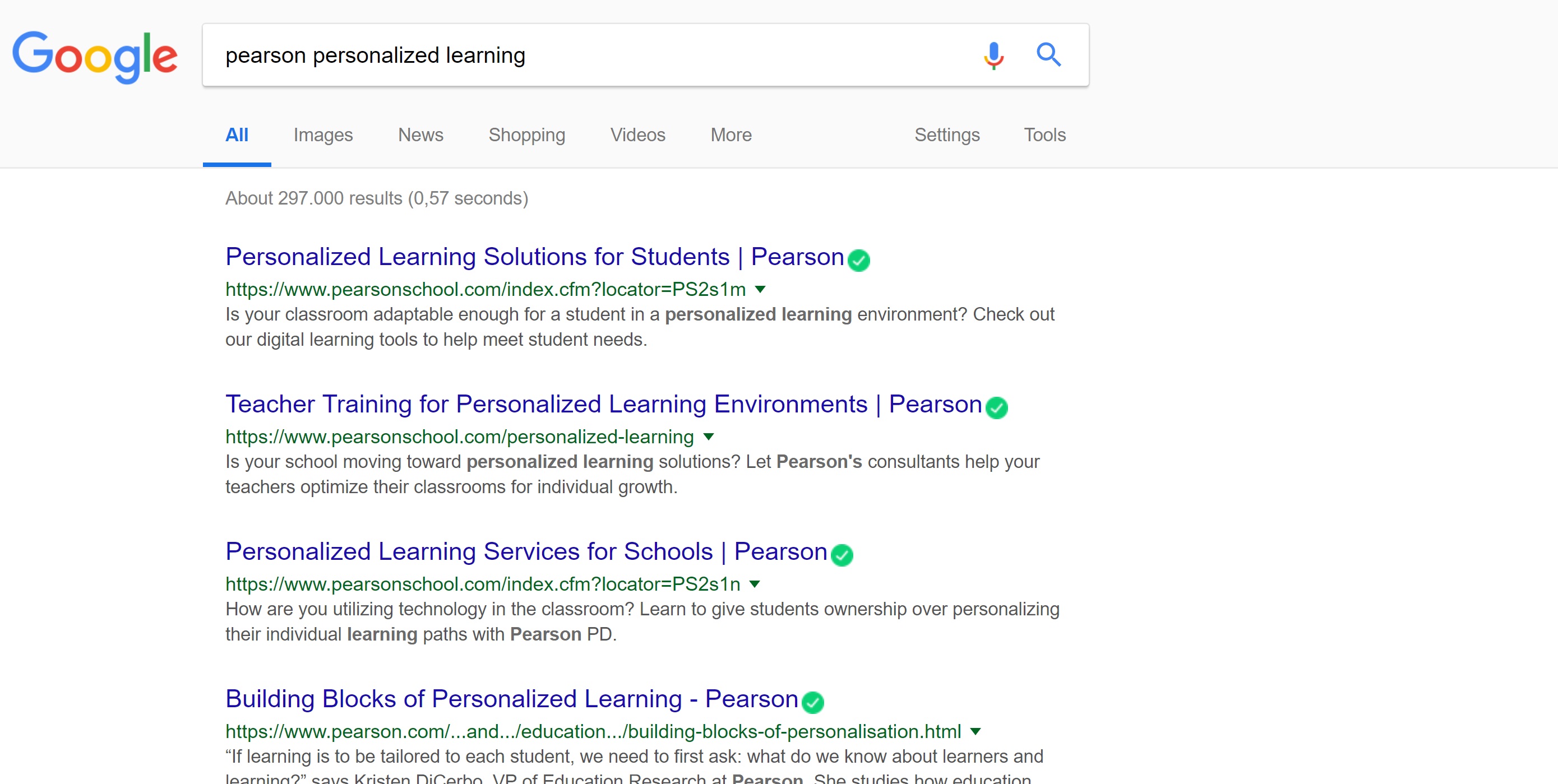

My first question was: how do conference presenters feel about personalised learning? One way of finding out is by looking at the adjectives that are found in close proximity. This is what you get. One of the most significant players in this field is Pearson, who have long been one of the most visible promoters of personalized learning (see the screen capture). At IATEFL, two of the ten conference abstracts which include the word ‘personalized’ are directly sponsored by Pearson. Pearson actually have ten presentations they have directly sponsored or are very closely associated with. Many of these do not refer to personalized learning in the abstract, but would presumably do so in the presentations themselves. There is, for example, a report on a professional development programme in Brazil using TDI (see above). There are two talks about the GSE, described as a tool ‘used to provide a personalised view of students’ language’. The marketing intent is clear: Pearson is to be associated with personalized learning (which is, in turn, associated with a variety of tech tools) – they even have a VP of data analytics, data science and personalized learning.

One of the most significant players in this field is Pearson, who have long been one of the most visible promoters of personalized learning (see the screen capture). At IATEFL, two of the ten conference abstracts which include the word ‘personalized’ are directly sponsored by Pearson. Pearson actually have ten presentations they have directly sponsored or are very closely associated with. Many of these do not refer to personalized learning in the abstract, but would presumably do so in the presentations themselves. There is, for example, a report on a professional development programme in Brazil using TDI (see above). There are two talks about the GSE, described as a tool ‘used to provide a personalised view of students’ language’. The marketing intent is clear: Pearson is to be associated with personalized learning (which is, in turn, associated with a variety of tech tools) – they even have a VP of data analytics, data science and personalized learning. It is also a marvellous example of propaganda, of the way that consent is manufactured. (If you haven’t read it yet, it’s probably time to read Herman and Chomsky’s ‘Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media’.) An excellent account of the way that consent for personalized learning has been manufactured can be found at

It is also a marvellous example of propaganda, of the way that consent is manufactured. (If you haven’t read it yet, it’s probably time to read Herman and Chomsky’s ‘Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media’.) An excellent account of the way that consent for personalized learning has been manufactured can be found at