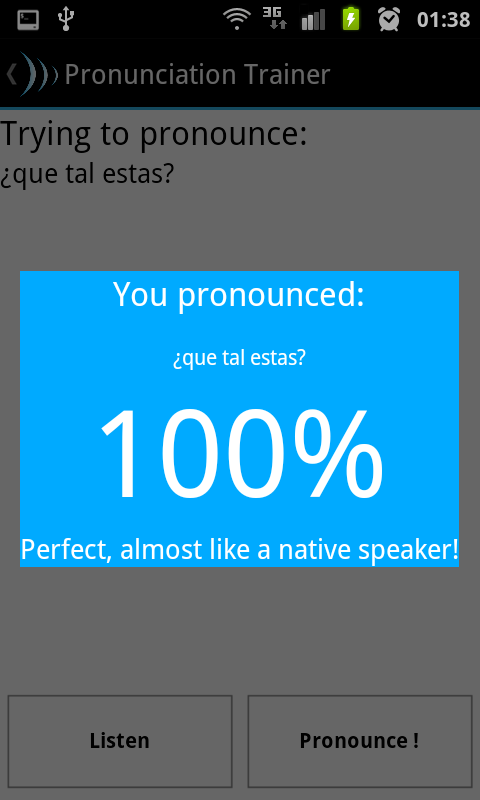

Recent years have seen a proliferation of computer-assisted pronunciations trainers (CAPTs), both as stand-alone apps and as a part of broader language courses. The typical CAPT records the learner’s voice, compares this to a model of some kind, detects differences between the learner and the model, and suggests ways that the learner may more closely approximate to the model (Agarwal & Chakraborty, 2019). Most commonly, the focus is on individual phonemes, rather than, as in Richard Cauldwell’s ‘Cool Speech’ (2012), on the features of fluent natural speech (Rogerson-Revell, 2021).

The fact that CAPTs are increasingly available and attractive ‘does not of course ensure their pedagogic value or effectiveness’ … ‘many are technology-driven rather than pedagogy-led’ (Rogerson-Revell, 2021). Rogerson-Revell (2021) points to two common criticisms of CAPTs. Firstly, their pedagogic accuracy sometimes falls woefully short. He gives the example of a unit on intonation in one app, where users are told that ‘when asking questions in English, our voice goes up in pitch’ and ‘we lower the pitch of our voice at the end of questions’. Secondly, he observes that CAPTs often adopt a one-size-fits-all approach, despite the fact that we know that issues of pronunciation are extremely context-sensitive: ‘a set of learners in one context will need certain features that learners in another context do not’ (Levis, 2018: 239).

There are, in addition, technical challenges that are not easy to resolve. Many CAPTs rely on automatic speech recognition (ASR), which can be very accurate with some accents, but much less so with other accents (including many non-native-speaker accents) (Korzekwa et al., 2022). Anyone using a CAPT will experience instances of the software identifying pronunciation problems that are not problems, and failing to identify potentially more problematic issues (Agarwal & Chakraborty, 2019).

We should not, therefore, be too surprised if these apps don’t always work terribly well. Some apps, like the English File Pronunciation app, have been shown to be effective in helping the perception and production of certain phonemes by a very unrepresentative group of Spanish learners of English (Fouz-González, 2020), but this tells us next to nothing about the overall effectiveness of the app. Most CAPTs have not been independently reviewed, and, according to a recent meta-analysis of CAPTs (Mahdi & Al Khateeb, 2019), the small number of studies are ‘all of very low quality’. This, unfortunately, renders their meta-analysis useless.

Even if the studies in the meta-analysis had not been of very low quality, we would need to pause before digesting any findings about CAPTs’ effectiveness. Before anything else, we need to develop a good understanding of what they might be effective at. It’s here that we run headlong into the problem of native-speakerism (Holliday, 2006; Kiczkowiak, 2018).

The pronunciation model that CAPTs attempt to push learners towards is a native-speaker model. In the case of ELSA Speak, for example, this is a particular kind of American accent, although ‘British and other accents’ will apparently soon be added. Xavier Anguera, co-founder and CTO of ELSA Speak, in a fascinating interview with Paul Raine of TILTAL, happily describes his product as ‘an app that is for accent reduction’. Accent reduction is certainly a more accurate way of describing CAPTs than accent promotion.

Accent reduction, or the attempt to mimic an imagined native-speaker pronunciation, is now ‘rarely put forward by teachers or researchers as a worthwhile goal’ (Levis, 2018: 33) because it is only rarely achievable and, in many contexts, inappropriate. In addition, accent reduction cannot easily be separated from accent prejudice. Accent reduction courses and products ‘operate on the assumption that some accents are more legitimate than others’ (Ennser-Kananen, et al., 2021) and there is evidence that they can ‘reinscribe racial inequalities’ (Ramjattan, 2019). Accent reduction is quintessentially native-speakerist.

Rather than striving towards a native-speaker accentedness, there is a growing recognition among teachers, methodologists and researchers that intelligibility may be a more appropriate learning goal (Levis, 2018) than accentedness. It has been over 20 years since Jennifer Jenkins (2000) developed her Lingua Franca Core (LFC), a relatively short list of pronunciation features that she considered central to intelligibility in English as a Lingua Franca contexts (i.e. the majority of contexts in which English is used). Intelligibility as the guiding principle of pronunciation teaching continues to grow in influence, spurred on by the work of Walker (2010), Kiczkowiak & Lowe (2018), Patsko & Simpson (2019) and Hancock (2020), among others.

Unfortunately, intelligibility is a deceptively simple concept. What exactly it is, is ‘not an easy question to answer’ writes John Levis (2018) before attempting his own answer in the next 250 pages. As admirable as the LFC may be as an attempt to offer a digestible and actionable list of key pronunciation features, it ‘remains controversial in many of its recommendations. It lacks robust empirical support, assumes that all NNS contexts are similar, and does not take into account the importance of stigma associated with otherwise intelligible pronunciations’ (Levis, 2018: 47). Other attempts to list features of intelligibility fare no better in Levis’s view: they are ‘a mishmash of incomplete and contradictory recommendations’ (Levis, 2018: 49).

Intelligibility is also complex because of the relationship between intelligibility and comprehensibility, or the listener’s willingness to understand – their attitude or stance towards the speaker. Comprehensibility is a mediation concept (Ennser-Kananen, et al., 2021). It is a two-way street, and intelligibility-driven approaches need to take this into account (unlike the accent-reduction approach which places all the responsibility for comprehensibility on the shoulders of the othered speaker).

The problem of intelligibility becomes even more thorny when it comes to designing a pronunciation app. Intelligibility and comprehensibility cannot easily be measured (if at all!), and an app’s algorithms need a concrete numerically-represented benchmark towards which a user / learner can be nudged. Accentedness can be measured (even if the app has to reify a ‘native-speaker accent’ to do so). Intelligibility / Comprehensibility is simply not something, as Xavier Anguera acknowledges, that technology can deal with. In this sense, CAPTs cannot avoid being native-speakerist.

At this point, we might ride off indignantly into the sunset, but a couple of further observations are in order. First of all, accentedness and comprehensibility are not mutually exclusive categories. Anguera notes that intelligibility can be partly improved by reducing accentedness, and some of the research cited by Levis (2018) backs him up on this. But precisely how much and what kind of accent reduction improves intelligibility is not knowable, so the use of CAPTs is something of an optimistic stab in the dark. Like all stabs in the dark, there are dangers. Secondly, individual language learners may be forgiven for not wanting to wait for accent prejudice to become a thing of the past: if they feel that they will suffer less from prejudice by attempting here and now to reduce their ‘foreign’ accent, it is not for me, I think, to pass judgement. The trouble, of course, is that CAPTs contribute to the perpetuation of the prejudices.

There is, however, one area where the digital evaluation of accentedness is, I think, unambiguously unacceptable. According to Rogerson-Revell (2021), ‘Australia’s immigration department uses the Pearson Test of English (PTE) Academic as one of five tests. The PTE tests speaking ability using voice recognition technology and computer scoring of test-takers’ audio recordings. However, L1 English speakers and highly proficient L2 English speakers have failed the oral fluency section of the English test, and in some cases it appears that L1 speakers achieve much higher scores if they speak unnaturally slowly and carefully’. Human evaluations are not necessarily any better.

References

Agarwal, C. & Chakraborty, P. (2019) A review of tools and techniques for computer aided pronunciation training (CAPT) in English. Education and Information Technologies, 24: 3731–3743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09955-7

Cauldwell, R (2012) Cool Speech app. Available at: http://www.speechinaction.org/cool-speech-2

Fouz-González, J (2020) Using apps for pronunciation training: An empirical evaluation of the English File Pronunciation app. Language Learning & Technology, 24(1): 62–85.

Ennser-Kananen, J., Halonen, M. & Saarinen, T. (2021) “Come Join Us and Lose Your Accent!” Accent Modification Courses as Hierarchization of International Students. Journal of International Students 11 (2): 322 – 340

Holliday, A. (2006) Native-speakerism. ELT Journal, 60 (4): 385 – 387

Jenkins. J. (2000) The Phonology of English as a Lingua Franca. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Hancock, M. (2020) 50 Tips for Teaching Pronunciation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Kiczkowiak, M. (2018) Native Speakerism in English Language Teaching: Voices From Poland. Doctoral dissertation.

Kiczkowiak, M & Lowe, R. J. (2018) Teaching English as a Lingua Franca. Stuttgart: DELTA Publishing

Korzekwa, D., Lorenzo-Trueba, J., Thomas Drugman, T. & Kostek, B. (2022) Computer-assisted pronunciation training—Speech synthesis is almost all you need. Speech Communication, 142: 22 – 33

Levis, J. M. (2018) Intelligibility, Oral Communication, and the Teaching of Pronunciation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Mahdi, H. S. & Al Khateeb, A. A. (2019) The effectiveness of computer-assisted pronunciation training: A meta-analysis. Review of Education, 7 (3): 733 – 753

Patsko, L. & Simpson, K. (2019) How to Write Pronunciation Activities. ELT Teacher 2 Writer https://eltteacher2writer.co.uk/our-books/how-to-write-pronunciation-activities/

Ramjattan, V. A. (2019) Racializing the problem of and solution to foreign accent in business. Applied Linguistics Review, 13 (4). https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev2019-0058

Rogerson-Revell, P. M. (2021) Computer-Assisted Pronunciation Training (CAPT): Current Issues and Future Directions. RELC Journal, 52(1), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220977406

Walker, R. (2010) Teaching the Pronunciation of English as a Lingua Franca. Oxford: Oxford University Press