Online teaching is big business. Very big business. Online language teaching is a significant part of it, expected to be worth over $5 billion by 2025. Within this market, the biggest demand is for English and the lion’s share of the demand comes from individual learners. And a sizable number of them are Chinese kids.

There are a number of service providers, and the competition between them is hot. To give you an idea of the scale of this business, here are a few details taken from a report in USA Today. VIPKid, is valued at over $3 billion, attracts celebrity investors, and has around 70,000 tutors who live in the US and Canada. 51Talk has 14,800 English teachers from a variety of English-speaking countries. BlingABC gets over 1,000 American applicants a month for its online tutoring jobs. There are many, many others.

Demand for English teachers in China is huge. The Pie News, citing a Chinese state media announcement, reported in September of last year that there were approximately 400,000 foreign citizens working in China as English language teachers, two-thirds of whom were working illegally. Recruitment problems, exacerbated by quotas and more stringent official requirements for qualifications, along with a very restricted desired teacher profile (white, native-speakers from a few countries like the US and the UK), have led more providers to look towards online solutions. Eric Yang, founder of the Shanghai-based iTutorGroup, which operates under a number of different brands and claims to be the ‘largest English-language learning institution in the world’, said that he had been expecting online tutoring to surpass F2F classes within a few years. With coronavirus, he now thinks it will come ‘much earlier’.

Typically, the work does not require much, if anything, in the way of training (besides familiarity with the platform), although a 40-hour TEFL course is usually preferred. Teachers deliver pre-packaged lessons. According to the USA Today report, Chinese students pay between $49 and $80 dollars an hour for the classes.

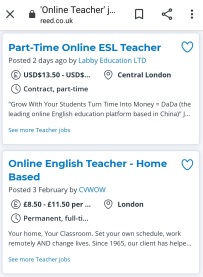

It’s a highly profitable business and the biggest cost to the platform providers is the rates they pay the tutors. If you google “Teaching TEFL jobs online”, you’ll quickly find claims that teachers can earn $40 / hour and up. Such claims are invariably found on the sites of recruitment agencies, who are competing for attention. However, although it’s possible that a small number of people might make this kind of money, the reality is that most will get nowhere near it. Scroll down the pages a little and you’ll discover that a more generally quoted and accepted figure is between $14 and $20 / hour. These tutors are, of course, freelancers, so the wages are before tax, and there is no health coverage or pension plan.

VIPKid, for example, considered to be one of the better companies, offers payment in the $14 – $22 / hour range. Others offer considerably less, especially if you are not a white, graduate US citizen. Current rates advertised on OETJobs include work for Ziktalk ($10 – 15 / hour), NiceTalk ($10 – 11 / hour), 247MyTutor ($5 – 8 / hour) and Weblio ($5 – 6 / hour). The number of hours that you get is rarely fixed and tutors need to build up a client base by getting good reviews. They will often need to upload short introductory videos, selling their skills. They are in direct competition with other tutors.

VIPKid, for example, considered to be one of the better companies, offers payment in the $14 – $22 / hour range. Others offer considerably less, especially if you are not a white, graduate US citizen. Current rates advertised on OETJobs include work for Ziktalk ($10 – 15 / hour), NiceTalk ($10 – 11 / hour), 247MyTutor ($5 – 8 / hour) and Weblio ($5 – 6 / hour). The number of hours that you get is rarely fixed and tutors need to build up a client base by getting good reviews. They will often need to upload short introductory videos, selling their skills. They are in direct competition with other tutors.

They also need to make themselves available when demand for their services is highest. Peak hours for VIPKid, for example, are between 2 and 8 in the morning, depending on where you live in the US. Weekends, too, are popular. With VIPKid, classes are scheduled in advance, but this is not always the case with other companies, where you log on to show that you are available and hope someone wants you. This is the case with, for example, Cambly (which pays $10.20 / hour … or rather $0.17 / minute) and NiceTalk. According to one review, Cambly has a ‘priority hours system [which] allows teachers who book their teaching slots in advance to feature higher on the teacher list than those who have just logged in, meaning that they will receive more calls’. Teachers have to commit to a set schedule and any changes are heavily penalised. The review states that ‘new tutors on the platform should expect to receive calls for about 50% of the time they’re logged on’.

Taking the gig economy to its logical conclusion, there are other companies where tutors can fix their own rates. SkimaTalk, for example, offers a deal where tutors first teach three unpaid lessons (‘to understand how the system works and build up their initial reputation on the platform’), then the system sets $16 / hour as a default rate, but tutors can change this to anything they wish. With another, Palfish, where tutors set their own rate, the typical rate is $10 – 18 / hour, and the company takes a 20% commission. With Preply, here is the deal on offer:

Your earnings depend on the hourly rate you set in your profile and how often you can provide lessons. Preply takes a 100% commission fee of your first lesson payment with every new student. For all subsequent lessons, the commission varies from 33 to 18% and depends on the number of completed lesson hours with students. The more tutoring you do through Preply, the less commission you pay.

Not one to miss a trick, Ziktalk (‘currently focusing on language learning and building global audience’) encourages teachers ‘to upload educational videos in order to attract more students’. Or, to put it another way, teachers provide free content in order to have more chance of earning $10 – 15 / hour. Ah, the joys of digital labour!

And, then, coronavirus came along. With schools shutting down, first in China and then elsewhere, tens of millions of students are migrating online. In Hong Kong, for example, the South China Morning Post reports that schools will remain closed until April 20, at the earliest, but university entrance exams will be going ahead as planned in late March. CNBC reported yesterday that classes are being cancelled across the US, and the same is happening, or is likely to happen, in many other countries.

Shares in the big online providers soared in February, with Forbes reporting that $3.2 billion had been added to the share value of China’s e-Learning leaders. Stock in New Oriental (owners of BlingABC, mentioned above) ‘rose 7.3% last month, adding $190 million to the wealth of its founder Yu Minhong [whose] current net worth is estimated at $3.4 billion’.

DingTalk, a communication and management app owned by Alibaba (and the most downloaded free app in China’s iOS App Store), has been adapted to offer online services for schools, reports Xinhua, the official state-run Chinese news agency. The scale of operations is enormous: more than 10,000 new cloud servers were deployed within just two hours.

Current impacts are likely to be dwarfed by what happens in the future. According to Terry Weng, a Shenzhen-based analyst, ‘The gradual exit of smaller education firms means there are more opportunities for TAL and New Oriental. […] Investors are more keen for their future performance.’ Zhu Hong, CTO of DingTalk, observes ‘the epidemic is like a catalyst for many enterprises and schools to adopt digital technology platforms and products’.

For edtech investors, things look rosy. Smaller, F2F providers are in danger of going under. In an attempt to mop up this market and gain overall market share, many elearning providers are offering weighty discounts and free services. Profits can come later.

For the hundreds of thousands of illegal or semi-legal English language teachers in China, things look doubly bleak. Their situation is likely to become even more precarious, with the online gig economy their obvious fall-back path. But English language teachers everywhere are likely to be affected one way or another, as will the whole world of TEFL.

Now seems like a pretty good time to find out more about precarity (see the Teachers as Workers website) and native-speakerism (see TEFL Equity Advocates).

Unconditional calls for language teachers to incorporate digital technology into their teaching are common. The reasons that are given are many and typically include the fact that (1) our students are ‘digital natives’ and expect technology to be integrated into their learning, (2) and digital technology is ubiquitous and has so many affordances for learning. Writing on the topic is almost invariably enthusiastic and the general conclusion is that the integration of technology is necessary and essential. Here’s a fairly typical example: digital technology is ‘an essential multisensory extension to the textbook’ (Torben Schmidt and Thomas Strasser in Surkamp & Viebrock, 2018: 221).

Unconditional calls for language teachers to incorporate digital technology into their teaching are common. The reasons that are given are many and typically include the fact that (1) our students are ‘digital natives’ and expect technology to be integrated into their learning, (2) and digital technology is ubiquitous and has so many affordances for learning. Writing on the topic is almost invariably enthusiastic and the general conclusion is that the integration of technology is necessary and essential. Here’s a fairly typical example: digital technology is ‘an essential multisensory extension to the textbook’ (Torben Schmidt and Thomas Strasser in Surkamp & Viebrock, 2018: 221).

Ventilla was an impressive money-raiser who used, and appeared to believe, every cliché in the edTech sales manual. Dressed in regulation jeans, polo shirt and fleece, he claimed that schools in America were ‘

Ventilla was an impressive money-raiser who used, and appeared to believe, every cliché in the edTech sales manual. Dressed in regulation jeans, polo shirt and fleece, he claimed that schools in America were ‘ More and more language learning is taking place, fully or partially, on online platforms and the affordances of these platforms for communicative interaction are exciting. Unfortunately, most platform-based language learning experiences are a relentless diet of drag-and-drop, drag-till-you-drop grammar or vocabulary gap-filling. The chat rooms and discussion forums that the platforms incorporate are underused or ignored. Lindsay Clandfield and Jill Hadfield’s new book is intended to promote online interaction between and among learners and the instructor, rather than between learners and software.

More and more language learning is taking place, fully or partially, on online platforms and the affordances of these platforms for communicative interaction are exciting. Unfortunately, most platform-based language learning experiences are a relentless diet of drag-and-drop, drag-till-you-drop grammar or vocabulary gap-filling. The chat rooms and discussion forums that the platforms incorporate are underused or ignored. Lindsay Clandfield and Jill Hadfield’s new book is intended to promote online interaction between and among learners and the instructor, rather than between learners and software.

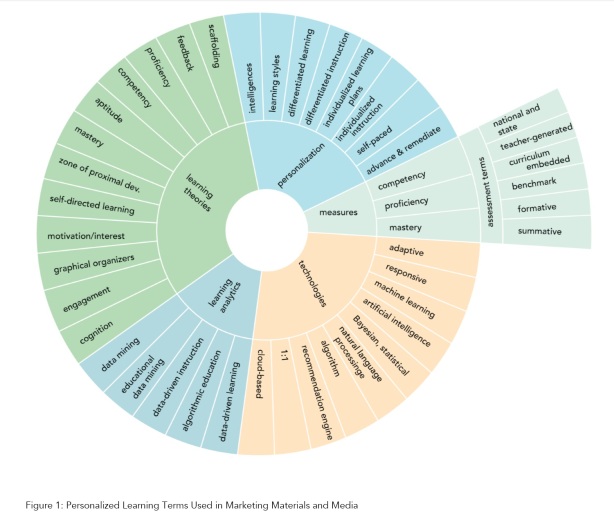

In the latest educational technology plan from the U.S. Department of Education (‘

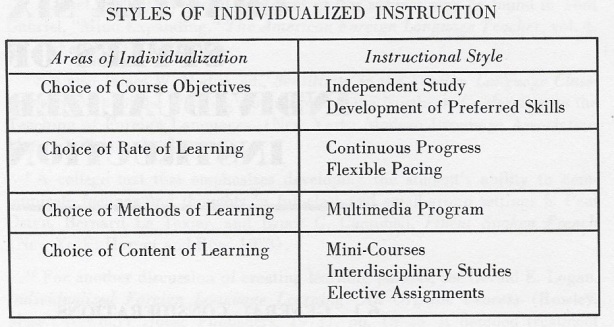

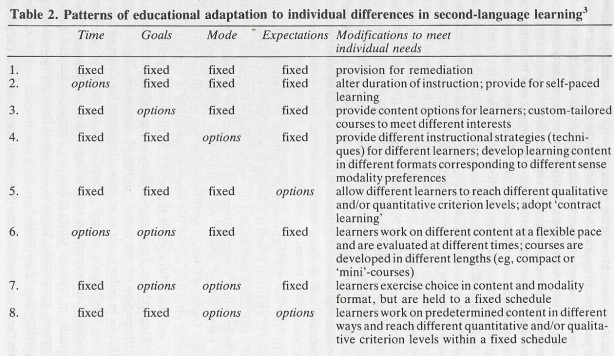

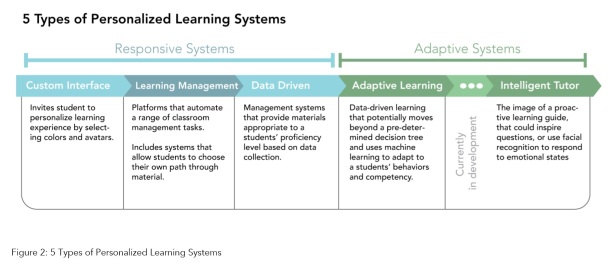

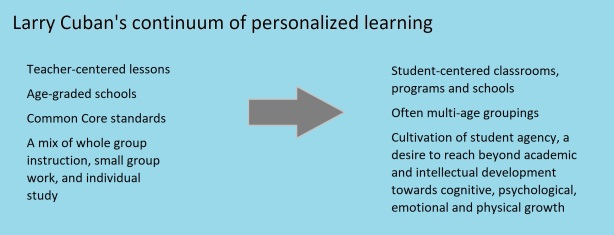

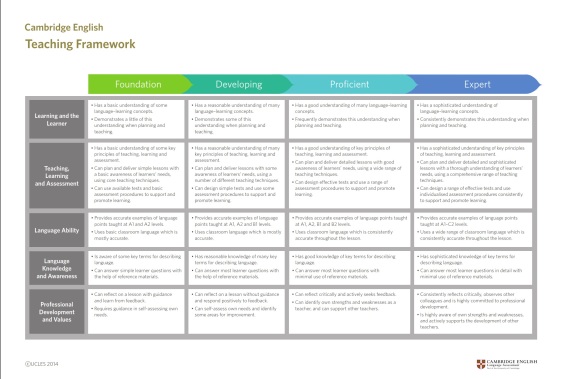

In the latest educational technology plan from the U.S. Department of Education (‘ The main point of adaptive learning tools is to facilitate differentiated instruction. They are, as

The main point of adaptive learning tools is to facilitate differentiated instruction. They are, as

Classroom practice could also form part of such an adaptive system. One tool that could be deployed would be

Classroom practice could also form part of such an adaptive system. One tool that could be deployed would be