In the last post, I suggested a range of activities that could be used in class to ‘activate’ a set of vocabulary before doing more communicative revision / recycling practice. In this, I’ll be suggesting a variety of more communicative tasks. As before, the activities require zero or minimal preparation on the part of the teacher.

1 Simple word associations

Write on the board a large selection of words that you want to recycle. Choose one word (at random) and ask the class if they can find another word on the board that they can associate with it. Ask one volunteer to (1) say what the other word is and (2) explain the association they have found between the two words. Then, draw a line through the first word and ask students if they can now choose a third word that they can associate with the second. Again, the nominated volunteer must explain the connection between the two words. Then, draw a line through the second word and ask for a connection between the third and fourth words. After three examples like this, it should be clear to the class what they need to do. Put the students into pairs or small groups and tell them to continue until there are no more words left, or it becomes too difficult to find connections / associations between the words that are left. This activity can be done simply in pairs or it can be turned into a class / group game.

As a follow-up, you might like to rearrange the pairs or groups and get students to see how many of their connections they can remember. As they are listening to the ideas of other students, ask them to decide which of the associations they found the most memorable / entertaining / interesting.

2 Association circles (variation of activity #1)

Ask students to look through their word list or flip through their flashcard set and make a list of the items that they are finding hardest to remember. They should do this with a partner and, together, should come up with a list of twelve or more words. Tell them to write these words in a circle on a sheet of paper.

Tell the students to choose, at random, one word in their circle. Next, they must find another word in the circle which they can associate in some way with the first word that they chose. They must explain this association to their partner. They must then find another word which they can associate with their second word. Again they must explain the association. They should continue in this way until they have connected all the words in their circle. Once students have completed the task with their partner, they should change partners and exchange ideas. All of this can be done orally.

3 Multiple associations

Using the same kind of circle of words, students again work with a partner. Starting with any word, they must find and explain an association with another word. Next, beginning with the word they first chose, they must find and explain an association with another word from the circle. They continue in this way until they have found connections between their first word and all the other words in the circle. Once students have completed the task with their partner, they should change partners and exchange ideas. All of this can be done orally.

4 Association dice

Prepare two lists (six in each list) of words that you want to recycle. Write these two lists on the board (list A and list B) with each word numbered 1 – 6. Each group in the class will need a dice.

First, demonstrate the activity with the whole class. Draw everyone’s attention to the two lists of the words on the board. Then roll a dice twice. Tell the students which numbers you have landed on. Explain that the first number corresponds to a word from List A and the second number to a word from List B. Think of and explain a connection / association between the two words. Organise the class into groups and ask them to continue playing the game.

Conduct feedback with the whole class. Ask them if they had any combinations of words for which they found it hard to think of a connection / association. Elicit suggestions from the whole class.

5 Picture associations #1

You will need a set of approximately eight pictures for this activity. These should be visually interesting and can be randomly chosen. If you do not have a set of pictures, you could ask the students to flick through their coursebooks and find a set of images that they find interesting or attractive. Tell them to note the page numbers. Alternatively, you could use pictures from the classroom: these might include posters on the walls, views out of the window, a mental picture of the teacher’s desk, a mental picture generated by imagining the whiteboard as a mirror, etc.

In the procedure described below, the students select the items they wish to practise. However, you may wish to select the items yourself. Make sure that students have access to dictionaries (print or online) during the lesson.

Ask the students to flip through their flashcard set or word list and make a list of the words that they are finding hardest to remember. They should do this with a partner and, together, should come up with a list of twelve or more words. The students should then find an association between each of the words on their list and one of the pictures that they select. They discuss their ideas with their partner, before comparing their ideas with a new partner.

6 Picture associations #2

Using the pictures and word lists (as in the activity above), students should select one picture, without telling their partner which picture they have selected. They should then look at the word list and choose four words from this list which they can associate with that picture. They then tell their four words to their partner, whose task is to guess which picture the other student was thinking of.

7 Rhyme associations

Prepare a list of approximately eight words that you want to recycle and write these on the board.

Ask the students to look at the words on the board. Tell them to work in pairs and find a word (in either English or their own language) which rhymes with each of the words on the list. If they cannot find a rhyming word, allow them to choose a word which sounds similar even if it is not a perfect rhyme.

The pairs should now find some sort of connection between each of the words on the list and their rhyming partners. When everyone has had enough time to find connections / associations, combine the pairs into groups of four, and ask them to exchange their ideas. Ask them to decide, for each word, which rhyming word and connection will be the most helpful in remembering this vocabulary.

Conduct feedback with the whole class.

8 Associations: truth and lies

In the procedure described below, no preparation is required. However, instead of asking the students to select the items they wish to practise, you may wish to select the items yourself. Make sure that students have access to dictionaries (print or online) during the lesson.

Ask students to flip through their flashcard set or word list and make a list of the words that they are finding hardest to remember. Individually, they should then write a series of sentences which contain these words: the sentences can contain one, two, or more of their target words. Half of the sentences should contain true personal information; the other half should contain false personal information.

Students then work with a partner, read their sentences aloud, and the partner must decide which sentences are true and which are false.

9 Associations: questions and answers

Prepare a list of between 12 and 20 items that you want the students to practise. Write these on the board (in any order) or distribute them as a handout.

Demonstrate the activity with the whole class before putting students into pairs. Make a question beginning with Why / How do you … / Why / How did you … / Why / How were you … which includes one of the target items from the list. The questions can be rather strange or divorced from reality. For example, if one of the words on the list were ankle, you could ask How did you break your ankle yesterday? Pretend that you are wracking your brain to think of an answer while looking at the other words on the board. Then, provide an answer, using one of the other words from the list. For example, if one of the other words were upset, you might answer I was feeling very upset about something and I wasn’t thinking about what I was doing. I fell down some steps. If necessary, do another example with the whole class to ensure that everyone understand the activity.

Tell the students to work in pairs, taking it in turns to ask and answer questions in the same way.

Conduct feedback with the whole class. Ask if there were any particularly strange questions or answers.

(I first came across a variation of this idea in a blog post by Alex Case ‘Playing with our Word Bag’

10 Associations: question and answer fortune telling

Prepare for yourself a list of items that you want to recycle. Number this list. (You will not need to show the list to anyone.)

Organise the class into pairs. Ask each pair to prepare four or five questions about the future. These questions could be personal or about the wider world around them. Give a few examples to make sure everyone understands: How many children will I have? What kind of job will I have five years from now? Who will win the next World Cup?

Tell the class that you have the answers to their questions. Hold up the list of words that you have prepared (without showing what is written on it). Elicit a question from one pair. Tell them that they must choose a number from 1 to X (depending on how many words you have on your list). Say the word aloud or write it on the board.

Tell the class that this is the answer to the question, but the answer must be ‘interpreted’. Ask the students to discuss in pairs the interpretation of the answer. You may need to demonstrate this the first time. If the question was How many children will I have? and the answer selected was precious, you might suggest that Your child will be very precious to you, but you will only have one. This activity requires a free imagination, and some classes will need some time to get used to the idea.

Continue with more questions and more answers selected blindly from the list, with students working in pairs to interpret these answers. Each time, conduct feedback with the whole class to find out who has the best interpretation.

11 Associations: narratives

In the procedure described below, no preparation is required. However, instead of asking the students to select the items they wish to practise, you may wish to select the items yourself. Make sure that students have access to dictionaries (print or online) during the lesson.

This activity often works best if it is used as a follow-up to ‘Picture Associations’. The story that the students prepare and tell should be connected to the picture that they focused on.

Ask students to flip through their flashcard set and make a list of the words that they are finding hardest to remember. They should do this with a partner and, together, should come up with a list of twelve or more words.

Still in pairs, they should prepare a short story which contains at least seven of the items in their list. After preparing their story, they should rehearse it before exchanging stories with another student / pair of students.

To extend this activity, the various stories can be ‘passed around’ the class in the manner of the game ‘Chinese Whispers’ (‘Broken Telephone’).

12 Associations: the sentence game

Prepare a list of approximately 25 items that you want the class to practise. Write these, in any order, on one side of the whiteboard.

Explain to the class that they are going to play a game. The object of the game is to score points by making grammatically correct sentences using the words on the board. If the students use just one of these words in a sentence, they will get one point. If they use two of the words, they’ll get two points. With three words, they’ll get three points. The more ambitious they are, the more points they can score. But if their sentence is incorrect, they will get no points and they will miss their turn. Tell the class that the sentences (1) must be grammatically correct, (2) must make logical sense, (3) must be single sentences. If there is a problem with a sentence, you, the teacher, will say that it is wrong, but you will not make a correction.

Put the class into groups of four students each. Give the groups some time to begin preparing sentences which contain one or more of the words from the list.

Ask a member from one group to come to the board and write one of the sentences they have prepared. If it is an appropriate sentence, award points. Cross out the word(s) that has been used from the list on the board: this word can no longer be used. If the sentence was incorrect, explain that there is a problem and turn to a member of the next group. This person can either (1) write a new sentence that their group has prepared, or (2) try, with the help of other members of their group to correct a sentence that is on the board. If their correction is correct, they score all the points for that sentence. If their correction is incorrect, they score no points and it is the end of their turn.

The game continues in this way with each group taking it in turns to make or correct sentences on the board.

(There are a number of comedy sketches about word associations. My favourite is this one. I’ve used it from time to time in presentations on this topic, but it has absolutely no pedagogical value (… unlike the next autoplay suggestion that was made for me, which has no comedy value).

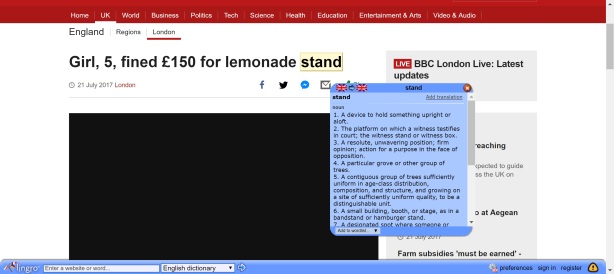

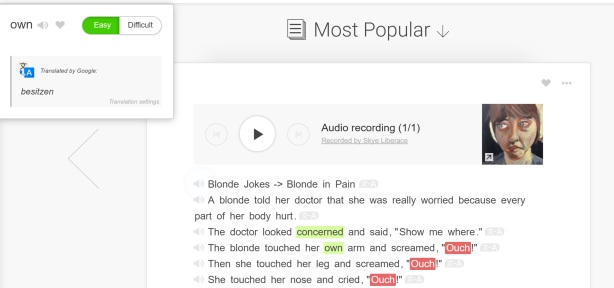

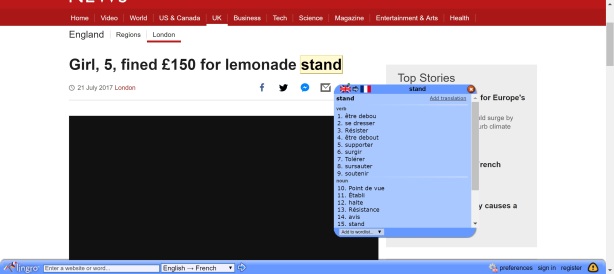

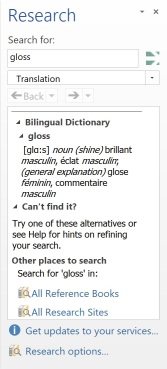

A gloss is ‘a brief definition or synonym, either in L1 or L2, which is provided with [a] text’ (Nation, 2013: 238). They can take many forms (e.g. annotations in the margin or at the foot a printed page), but electronic or CALL glossing is ‘an instant look-up capability – dictionary or linked’ (Taylor, 2006; 2009) which is becoming increasingly standard in on-screen reading. One of the most widely used is probably the translation function in Microsoft Word: here’s the French gloss for the word ‘gloss’.

A gloss is ‘a brief definition or synonym, either in L1 or L2, which is provided with [a] text’ (Nation, 2013: 238). They can take many forms (e.g. annotations in the margin or at the foot a printed page), but electronic or CALL glossing is ‘an instant look-up capability – dictionary or linked’ (Taylor, 2006; 2009) which is becoming increasingly standard in on-screen reading. One of the most widely used is probably the translation function in Microsoft Word: here’s the French gloss for the word ‘gloss’.