Online teaching is big business. Very big business. Online language teaching is a significant part of it, expected to be worth over $5 billion by 2025. Within this market, the biggest demand is for English and the lion’s share of the demand comes from individual learners. And a sizable number of them are Chinese kids.

There are a number of service providers, and the competition between them is hot. To give you an idea of the scale of this business, here are a few details taken from a report in USA Today. VIPKid, is valued at over $3 billion, attracts celebrity investors, and has around 70,000 tutors who live in the US and Canada. 51Talk has 14,800 English teachers from a variety of English-speaking countries. BlingABC gets over 1,000 American applicants a month for its online tutoring jobs. There are many, many others.

Demand for English teachers in China is huge. The Pie News, citing a Chinese state media announcement, reported in September of last year that there were approximately 400,000 foreign citizens working in China as English language teachers, two-thirds of whom were working illegally. Recruitment problems, exacerbated by quotas and more stringent official requirements for qualifications, along with a very restricted desired teacher profile (white, native-speakers from a few countries like the US and the UK), have led more providers to look towards online solutions. Eric Yang, founder of the Shanghai-based iTutorGroup, which operates under a number of different brands and claims to be the ‘largest English-language learning institution in the world’, said that he had been expecting online tutoring to surpass F2F classes within a few years. With coronavirus, he now thinks it will come ‘much earlier’.

Typically, the work does not require much, if anything, in the way of training (besides familiarity with the platform), although a 40-hour TEFL course is usually preferred. Teachers deliver pre-packaged lessons. According to the USA Today report, Chinese students pay between $49 and $80 dollars an hour for the classes.

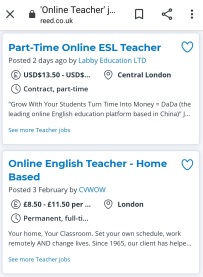

It’s a highly profitable business and the biggest cost to the platform providers is the rates they pay the tutors. If you google “Teaching TEFL jobs online”, you’ll quickly find claims that teachers can earn $40 / hour and up. Such claims are invariably found on the sites of recruitment agencies, who are competing for attention. However, although it’s possible that a small number of people might make this kind of money, the reality is that most will get nowhere near it. Scroll down the pages a little and you’ll discover that a more generally quoted and accepted figure is between $14 and $20 / hour. These tutors are, of course, freelancers, so the wages are before tax, and there is no health coverage or pension plan.

VIPKid, for example, considered to be one of the better companies, offers payment in the $14 – $22 / hour range. Others offer considerably less, especially if you are not a white, graduate US citizen. Current rates advertised on OETJobs include work for Ziktalk ($10 – 15 / hour), NiceTalk ($10 – 11 / hour), 247MyTutor ($5 – 8 / hour) and Weblio ($5 – 6 / hour). The number of hours that you get is rarely fixed and tutors need to build up a client base by getting good reviews. They will often need to upload short introductory videos, selling their skills. They are in direct competition with other tutors.

VIPKid, for example, considered to be one of the better companies, offers payment in the $14 – $22 / hour range. Others offer considerably less, especially if you are not a white, graduate US citizen. Current rates advertised on OETJobs include work for Ziktalk ($10 – 15 / hour), NiceTalk ($10 – 11 / hour), 247MyTutor ($5 – 8 / hour) and Weblio ($5 – 6 / hour). The number of hours that you get is rarely fixed and tutors need to build up a client base by getting good reviews. They will often need to upload short introductory videos, selling their skills. They are in direct competition with other tutors.

They also need to make themselves available when demand for their services is highest. Peak hours for VIPKid, for example, are between 2 and 8 in the morning, depending on where you live in the US. Weekends, too, are popular. With VIPKid, classes are scheduled in advance, but this is not always the case with other companies, where you log on to show that you are available and hope someone wants you. This is the case with, for example, Cambly (which pays $10.20 / hour … or rather $0.17 / minute) and NiceTalk. According to one review, Cambly has a ‘priority hours system [which] allows teachers who book their teaching slots in advance to feature higher on the teacher list than those who have just logged in, meaning that they will receive more calls’. Teachers have to commit to a set schedule and any changes are heavily penalised. The review states that ‘new tutors on the platform should expect to receive calls for about 50% of the time they’re logged on’.

Taking the gig economy to its logical conclusion, there are other companies where tutors can fix their own rates. SkimaTalk, for example, offers a deal where tutors first teach three unpaid lessons (‘to understand how the system works and build up their initial reputation on the platform’), then the system sets $16 / hour as a default rate, but tutors can change this to anything they wish. With another, Palfish, where tutors set their own rate, the typical rate is $10 – 18 / hour, and the company takes a 20% commission. With Preply, here is the deal on offer:

Your earnings depend on the hourly rate you set in your profile and how often you can provide lessons. Preply takes a 100% commission fee of your first lesson payment with every new student. For all subsequent lessons, the commission varies from 33 to 18% and depends on the number of completed lesson hours with students. The more tutoring you do through Preply, the less commission you pay.

Not one to miss a trick, Ziktalk (‘currently focusing on language learning and building global audience’) encourages teachers ‘to upload educational videos in order to attract more students’. Or, to put it another way, teachers provide free content in order to have more chance of earning $10 – 15 / hour. Ah, the joys of digital labour!

And, then, coronavirus came along. With schools shutting down, first in China and then elsewhere, tens of millions of students are migrating online. In Hong Kong, for example, the South China Morning Post reports that schools will remain closed until April 20, at the earliest, but university entrance exams will be going ahead as planned in late March. CNBC reported yesterday that classes are being cancelled across the US, and the same is happening, or is likely to happen, in many other countries.

Shares in the big online providers soared in February, with Forbes reporting that $3.2 billion had been added to the share value of China’s e-Learning leaders. Stock in New Oriental (owners of BlingABC, mentioned above) ‘rose 7.3% last month, adding $190 million to the wealth of its founder Yu Minhong [whose] current net worth is estimated at $3.4 billion’.

DingTalk, a communication and management app owned by Alibaba (and the most downloaded free app in China’s iOS App Store), has been adapted to offer online services for schools, reports Xinhua, the official state-run Chinese news agency. The scale of operations is enormous: more than 10,000 new cloud servers were deployed within just two hours.

Current impacts are likely to be dwarfed by what happens in the future. According to Terry Weng, a Shenzhen-based analyst, ‘The gradual exit of smaller education firms means there are more opportunities for TAL and New Oriental. […] Investors are more keen for their future performance.’ Zhu Hong, CTO of DingTalk, observes ‘the epidemic is like a catalyst for many enterprises and schools to adopt digital technology platforms and products’.

For edtech investors, things look rosy. Smaller, F2F providers are in danger of going under. In an attempt to mop up this market and gain overall market share, many elearning providers are offering weighty discounts and free services. Profits can come later.

For the hundreds of thousands of illegal or semi-legal English language teachers in China, things look doubly bleak. Their situation is likely to become even more precarious, with the online gig economy their obvious fall-back path. But English language teachers everywhere are likely to be affected one way or another, as will the whole world of TEFL.

Now seems like a pretty good time to find out more about precarity (see the Teachers as Workers website) and native-speakerism (see TEFL Equity Advocates).

“English language teachers everywhere are likely to be affected one way or another, as will the whole world of TEFL”

What these online service providers and “celebrity investors” seem to have overlooked is how much all this will rely on various Ministries of Education.

While real-time translation and interpreting software still has some ways to go, I’m told it is advancing in quality and accuracy at an exponential rate.

I mention this because one thing I’m curious about is the proportion of these online teachers of English that are fully conversant, or at least have a B2 level of competence, in the language of the learners they are reaching over the Internet.

It’s all too easy to imagine, say, a Chinese teenager with a relatively limited proficiency in English making use of machine translation tools of one kind of another to help grease the wheels of the lesson with a tutor of English from Canada or Germany who has little or no knowledge of Chinese.

At that point, the teenager might be forgiven for pondering the use of learning English at all if so much of their formative experiences of L2 language use would be mediated through and heavily dependent on digital translation and interpreting tools.

At a guess, the answer would have to be the Ministry of Education requires students to demonstrate a certain proficiency in the language, independently and largely or wholly unaided by props such as translation software.

But at some point, presumably the Ministry of Education itself might start to wonder what the point of evaluating foreign language skills are if everyone is using such technology.

It might be the case that at that point, the balance struck between being a user of English as a practical ability in the goings on in everyday life and business on the one hand, and as a marker of social class and entry into a prestige class tips away from the former and towards the latter.

In many countries, a fluency in English as an L2 is already a marker of class and status, but it still has functional value in all kinds of ways.

If that functional value as a lingua franca declines, the more the learning of English as an L2 would need to be propped up by institutional support in the form of e.g. university entrance examinations.

Naturally, I’m exaggerating to some degree and, besides, like most people I’m wary of predictions about the future in general, but even so …

…. I think the important point that the investors seem to have missed is that the reasons why someone might need to learn a language are changing and likely to change further still as a direct consequence of the very same technologies they’re now using to deliver lessons.

But I suppose a good profit can still be turned in the medium-term.

Well, that’s certainly true.

But I’d be interested to see how much they might be incentivized to influence the Ministry of Education’s policy (if and when the time comes that proficiency of an L2 comes to be more about status or prestige and less about functional use).

I think if we look at current levels of influence from business interests in educational policies, we can be pretty sure how things will go. Get rid of English and devote more time to C21 skills (especially resilience)!

On the use of DingTalk for students in China, Wang Xiuying in the LRB says:

“Children were presumably glad to be off school – until, that is, an app called DingTalk was introduced. Students are meant to sign in and join their class for online lessons; teachers use the app to set homework. Somehow the little brats worked out that if enough users gave the app a one-star review it would get booted off the App Store. Tens of thousands of reviews flooded in, and DingTalk’s rating plummeted overnight from 4.9 to 1.4. The app has had to beg for mercy on social media: ‘I’m only five years old myself, please don’t kill me.’”

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v42/n05/wang-xiuying/the-word-from-wuhan

[…] But the online kids teaching market is growing massively. As Philip Kerr wrote recently, […]

Read this! https://wordpress.com/read/feeds/15648226/posts/2647253405

This article looks at the way that digital health companies are making the most of the COVID-19 crisis: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/03/coronavirus-covid-tech-firms-telehealth It makes an interesting parallel to what edtech is currently up to. cf. the article by Ben Williamson in the link in my previous comment.

And here’s a good article by Naomi Klein on the same topic: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2020/may/13/naomi-klein-how-big-tech-plans-to-profit-from-coronavirus-pandemic

And another article by Mariya Ivancheva on the same topic: https://www.brexitblog-rosalux.eu/2020/05/21/a-perfect-storm-uk-universities-covid-19-and-the-edtech-peril/

More COVID edtech news, this time from Brazil – ‘World Bank pushes privatized distance learning in Brazil’ https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2020/06/29/braz-j29.html