‘Whenever a word is frequently used in arguments trying to persuade people to believe some opinion or other, our mental twists and turns to make the opinion plausible involve shifting from meaning to meaning without realizing it. This has happened to creativity on a grand scale.’ (Perry, L. (1987). The Educational Value of Creativity. Journal of Art and Design Education 6 (3) ) quoted in Pugliese, 2010: 8)

If you take a look at the word ‘creativity’ in Google’s Ngram viewer, you’ll notice that use of the word really took off around 1950, the year when J. P. Guilford published an article entitled ‘Creativity’ in American Psychologist. Guilford’s background was in the US military. His research was part funded by the US Navy and his subjects were US Air Force personnel. His interest was in the classification and training of military recruits.

With the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union hotting up, Guilford’s interests increasingly became a matter of national security. In 1954, Carl Rogers, argued that education tended to turn out ‘conformists […] rather than freely creative and original thinkers’ (Rogers, 1954: 249) and that there was a ‘desperate need’ for the latter. He warned that ‘international annihilation will be the price we pay for a lack of creativity’. When Sputnik scared the shit out of the American military, creativity became more important still. It ‘could no longer be left to the chance occurrence of genius; neither could it be left in the realm of the wholly mysterious and the untouchable. Men had to be able to do something about it; creativity had to be a property in many men; it had to be something identifiable; it had to be subject to efforts to gain more of it’ (Razik, 1967).

It wasn’t long before creativity moved beyond purely military concerns to more generally corporate ones. Creativity became one of the motors driving the economy. This process is tracked in a fascinating article by Steven Shapin (2020), who quotes the director of research at General Electric as saying in 1959: ‘I think we can agree at once that we are all in favour of creativity’. Since then, the idea of creativity has rarely looked back.

By the end of the century, the UK government had set up a National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education, chaired by Ken Robinson. Creativity was seen as a ‘vital investment in human capital for the twenty-first century’ (National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education, 1999). Quoting the prime minister, Blair, the report stated that ‘our aim must be to create a nation where the creative talents of all the people are used to build a true enterprise economy for the twenty-first century — where we compete on brains, not brawn’.

A few years later, in the US, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills was founded, supported primarily by the corporate community with companies like AOL Time Warner, Apple and Microsoft providing financial backing. The ‘21st century skills’ required by global employers (or more specifically that global employers wanted national governments to pay for) could be catchily boiled down to the 4Cs – communication, collaboration, critical reflection and creativity. What was meant by creativity is made clearer in Trilling and Fadel’s bible of 21st century skills (2009: 56):

‘Given the 21st century demands to continuously innovate new services, better processes, and improved products for the world’s global economy, and for the creative knowledge required in more and more of the world’s better-paying jobs, it should come as no surprise that creativity and innovation are very high on the list of 21st century skills. In fact, many believe that our current Knowledge Age is quickly giving way to an Innovation Age, where the ability to solve problems in new ways (like the greening of energy use), to invent new technologies (like bio- and nanotechnology) or create the new killer application of existing technologies (like efficient and affordable electric cars and solar panels, or even to discover new branches of knowledge and invent entirely new industries, will all be highly prized.’

In this line of thought, creativity is blurred with ‘innovation skills’ and inextricably linked to business (and employee) performance. It involves creative thinking techniques (such as brainstorming), the ability to work collaboratively and creatively with others, openness to new ideas and perspectives, originality and inventiveness in work, and understanding real-world limits to adopting new ideas (Trilling & Fadel, 2009: 59). Although never defined very precisely, the purpose of creativity in education (as well as 21st skills more generally) is crystal-clear:

‘A fundamental role of education is to equip students with the competences they need – and will need – in order to succeed in society. Creative thinking is a necessary competence for today’s young people to develop. It can help them adapt to a constantly and rapidly changing world, and one that demands flexible workers equipped with ‘21st century’ skills that go beyond core literacy and numeracy. After all, children today will likely be employed in sectors or roles that do not yet exist’. (OECD, 2019: 6)

Creativity, then, has become first and foremost about the development of human capital and, by extension, the health of financial capital. In the World Economic Forum’s list of ‘5 Things You Need To Know About Creativity’, #1 on the list is ‘Creativity is good for the Economy’, #4 is ‘It’s important for leadership’, and #5 is ‘It’s crucial for the future of work’. For the World Bank, creativity is more or less synonymous with entrepreneurship (World Bank, 2010).

Given the importance that the OECD attaches to creativity, it was inevitable that they should seek to measure it. The next round of PISA tests, postponed to 2022 because of Covid-19, will incorporate evaluation of creative thinking. As the OECD itself recognises (OECD, 2019), this will be no easy task. There are problems in establishing a valid and agreed construct of creative thinking / creativity. There is debate about the extent to which creative thinking is domain-specific (does creative thinking in science different to creative thinking in the arts?). Previous attempts to measure creativity have been less than satisfactory. But none of this will stop the OECD juggernaut, and shortcomings in the first round of evaluations can be taken, creatively, as ‘an opportunity to learn’ (Trilling & Fadel, 2009: 59). There will be a washback effect, but this is all to the good in the eyes of the OECD. One of their most significant objectives in measuring creativity is to encourage ‘changes in education policies and pedagogies’ (OECD, 2019: 5): ‘the results will also encourage a wider societal debate on both the importance and methods of supporting this crucial competence through education’. To a large extent, it is an agenda-setting exercise.

Creativity’s most well-known cheerleader is the late Ken Robinson. His advocacy of creativity in education for the purposes of developing human capital is clear from his contribution to the National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education (1999) report. Subsequently, he changed his tune a little, and was careful to expand on his reasons for promoting creativity. Creativity, for Robinson, became something of broader importance than it was for those with a 21st century skills agenda. ‘There’s a lot of talk these days about 21st century skills,’ he said, ‘and I go along with a great deal of it, my only reservation about the idea of 21st century skills is that when they’re listed, they often include skills that were relevant at any time, in any century, it’s not that they’re a completely brand new set of things that people need to learn now that they didn’t have to learn before, but the context is very different’. In another interview, when pushed about creativity as an ‘essential 21st century skill’ – ‘why is creativity especially important right now?’ – Robinson again avoided going too far down the 21st century skills path. In reply, he offered a number of reasons, but the economy was the last that he mentioned. Human capital mattered to Robinson (‘any conversation about education that doesn’t take account of the economy is really, in some respects, detached and naïve from the world that we live in’ he said in another interview), but he made a point of downplaying it. As a highly accomplished rhetorician, Robinson knew how to tailor his messages for his audiences. His success and fame were due in large part to his ability to craft messages for everybody, and his readiness to allow the significance of creativity to shift from one meaning to another played, in my view, a large role in his appeal.

In ELT, there is no doubt that creativity is, as Maley and Kiss (2018: v) put it, ‘a fashionable concept’. In addition to Maley & Kiss’s ‘Creativity and English Language Teaching’ (2018), recent publications have included ‘The Creative Teacher’s Compendium’ (Clare & Marsh, 2020), ‘Hacking Creativity’ (Peachey, 2019), ‘50 Creative Activities’ (Maley, 2018), ‘Creativity in English Language Teaching’ (Xerri & Vassallo, 2016), ‘Creativity in the English language classroom’ (Maley & Peachey, 2015) and ‘Being Creative’ (Pugliese, 2010). In addition, there have been chapters on creativity in recent books about 21st century skills in ELT, such as ‘21st Century Skills in the ELT Classroom – A Guide for Teachers’ (Graham, 2020) and ‘English for 21st Century Skills’ (Mavridi & Xerri, 2020). Robinson is regularly cited.

What is striking about all these publications is that the kind of creativity that is promoted has virtually nothing to do with the kind of creativity that has been discussed in the first part of this article. The notion of language learners as human capital is absent, the purpose of creativity teaching is entirely different, and the creativity of the 4 Cs of 21st century skills has transformed into something else altogether. Even in the edited collections with ‘21st century skills’ in their titles, creativity has little or nothing to do with the creativity of the OECD. In most of these titles, ‘21st century skills’ are not mentioned at all, or only briefly in passing. In the 330 pages of Maley and Kiss (2018), for example, there are only three mentions of the term.

Instead, we have something that is not very ‘21st century’ at all. Definitions of creativity in these ELT books are very broad, and acknowledge the problems in even providing a definition. Recognising these difficulties, Nik Peachey (2019: iv) doesn’t even attempt to provide a definition. Instead, he offers a selection of ideas and activities which have something to do with the concept. Maley (in Xerri & Vassallo, 2016: 10) takes a similar approach, offering a list of attributes, including things like newness / originality, immediacy, wonder, curiosity / play, inspiration, finding / making connections, unpredictability, relevance and flow. Pugliese (2010: 114) asks teachers how they interpret creativity and this list includes problem-solving, the teacher’s aesthetic drive, a combination of the previous two, and a search for Rogerian self-actualization. Both writers focus heavily on the teacher’s own commitment to creativity. For Pugliese (2010: 12), ‘creativity is about wanting to be creative’.

In practice, the classroom ideas that are on offer can usually be put into one or more of the following categories:

- Activities that involve the arts: drama, stories, music, song, chants, poetry and dance, etc. Maley (2018) is especially interested in poetry, and Pugliese (2010) explores music and the visual arts in more detail.

- Activities that involves the learners in personalized self-expression, with emotional responses prioritized.

- Activities which are in some way exploratory, unpredictable or ‘different’. The work of John Fanselow (e.g. 1987) is an important inspiration here.

The overall result is a relabelled mash-up of ideas that have been around for some time: exploitation of literature, music and art; humanistic approaches inspired by Stevick, Rinvolucri and others; a sprinkling of positive psychology; and, sometimes, suggestions for using digital technology to facilitate creative expression of some kind. I hope I am not being unfair if I suggest that the problem of definition arises because the 21st century label of creativity has been stuck on bottles of vintage wine.

Most of these writers seem content to ignore 21st century OECD-style creativity, to pretend that it is not the driver of the ‘fashionable concept’ they are writing about. However, the reason for this silence surfaces from time to time: most of these ELT writers disapprove of, even dislike, the OECD version of creativity. Here, for example, is Chris Kennedy in the foreword to Maley & Peachey (2015: 2):

‘It is worrying in our market-driven world that […] certain concepts, and the words used to express them, lose their value through over-use or ill-definition. […] The danger is that such terms may be hijacked by public bodies and private institutions which employ them as convenient but opaque policy pegs on which practitioners, including educators, are expected to hang their approaches and behaviours. ‘Creativity’ is one such term, and UK government reports on the subject in the last few years show the concept of creativity being used to support a particular instrumental political view as a means of promoting the economy, rather than as a focus for developing individual skills and talents.’

And here’s David Nunan (in Mavridi & Xerri, 2020: 6) dishing out some vitriol:

‘I have been unable to find any evidence that the ability to solve such [problem-solving 21st century-style creativity tasks] transfers to the ability to solve such problems in real life. This has not stopped some people building their careers out of the concept and amassing considerable compensation in the process. Robinson even garnered a knighthood’.

This is all rather strange. It is creativity as a 21st century skill that has made the topic a ‘fashionable concept’. The ideas of Alan Maley et al about creativity become more plausible because the meaning of the key term can shift around. His book (with Nik Peachey) was commissioned by the British Council, an organisation that is profoundly committed to the idea that 21st century skills, including creativity, are essential for young people ‘to be fully prepared for life and work in a global economy’. In this light, Maley & Peachey (2015), which kicks off with a Maley poem before the Chris Kennedy foreword, may almost be seen as a subversive hijacking, a détournement of British Council discourse. But détourneurs can be détourné in their turn …

Maley’s co-author, Tamas Kiss, on ‘Creativity and English Language Teaching’, a book which so strenuously avoided the discourse of 21st century creativity, chose to discuss this work in the following way for a webpage for his university:

‘Dr Kiss explained that creativity has been the subject of investigation in several fields including psychology and business, as well as language teaching, and is one of the ‘core skills’ of most 21st century educational frameworks:

“People have realised that traditional knowledge transfer systems are not necessarily preparing students for 21st century jobs,” said Tamas, “New educational frameworks, for example those developed by the Council of Europe, emphasize cross-cultural communication, problem-solving, and creativity.”’

The university in question is Xi’an Jiaotong University, to the west of Shanghai. In the same year as the publication of the book that Kiss co-authored with Maley, Barbara Schulte gave a conference presentation entitled ‘Appropriating or hijacking creativity? Educational reform and creative learning in China’ (Schulte, 2018). She noted the increasing importance accorded to creativity in China’s educational reforms, the country’s increasing engagement with OECD benchmarks, and the way in which creative approaches ‘originally intended to empower learners are turned into their exact opposites, constraining learners’ spaces even more than with conventional approaches’.

Creativity is a classic weasel word. Its use should come accompanied with a hazard warning.

References

Clare, A. & Marsh, A. (2020). The Creative Teacher’s Compendium. Teddington, Middx.: Pavilion

Fanselow, J. (1987). Breaking Rules. Harlow: Longman

Graham, C. (Ed.) (2020). 21st Century Skills in the ELT Classroom – A Guide for Teachers. Reading: Granet

Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5 (9): pp.444–454

Maley, A. (2018). Alan Maley’s 50 Creative Activities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Maley, A. & Kiss, T. (2018). Creativity and English Language Teaching. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Maley, A. & Peachey, N. (Eds.) (2015). Creativity in the English language classroom. London: British Council

Mavridi, S. & Xerri, D. (Eds.) English for 21st Century Skills. Newbury, Berks.: Express Publishing

National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education. (1999). All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education http://sirkenrobinson.com/pdf/allourfutures.pdf

OECD (2019). PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Framework (Third Draft). Paris: OECD.

Peachey, N. (2019). Hacking Creativity. PeacheyPublications.

Pugliese, C. (2010). Being Creative. Peaslake: DELTA

Razik, T. A. (1967). Psychometric measurement of creativity. In Mooney, R. L. & Razik, T. A. (Eds.) Explorations in Creativity. New York: Harper & Row

Rogers, C. (1954). Toward a Theory of Creativity. ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 11: pp. 249-260

Schulte, B. (2018). Appropriating or hijacking creativity? Educational reform and creative learning in China. Abstract from Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE) Conference 2018, Sydney, Australia.

Shapin, S. (2020). The rise and rise of creativity. Aeon 12 October 2020 https://aeon.co/essays/how-did-creativity-become-an-engine-of-economic-growth

Trilling, B. & Fadel, C. (2009). 21st Century Skills. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

World Bank (2010). Stepping Up Skills. Washington: The World Bank

Xerri, D. & Vassallo, O. (Eds.) (2016). Creativity in English Language Teaching. Floriana: ELT Council

VIPKid, for example, considered to be one of the better companies, offers payment in the $14 – $22 / hour range. Others offer considerably less, especially if you are not a white, graduate US citizen. Current rates advertised on

VIPKid, for example, considered to be one of the better companies, offers payment in the $14 – $22 / hour range. Others offer considerably less, especially if you are not a white, graduate US citizen. Current rates advertised on

Over the last week, the Guardian has been running

Over the last week, the Guardian has been running  Although hammers are not usually classic examples of educational technology, they are worthy of a short discussion. Hammers come in all shapes and sizes and when you choose one, you need to consider its head weight (usually between 16 and 20 ounces), the length of the handle, the shape of the grip, etc. Appropriate specifications for particular hammering tasks have been calculated in great detail. The data on which these specifications is based on an analysis of the hand size and upper body strength of the typical user. The typical user is a man, and the typical hammer has been designed for a man. The average male hand length is 177.9 mm, that of the average woman is 10 mm shorter (Wang & Cai, 2017). Women typically have about half the upper body strength of men (Miller et al., 1993). It’s possible, but not easy to find hammers designed for women (they are referred to as ‘Ladies hammers’ on Amazon). They have a much lighter head weight, a shorter handle length, and many come in pink or floral designs. Hammers, in other words, are far from neutral: they are highly gendered.

Although hammers are not usually classic examples of educational technology, they are worthy of a short discussion. Hammers come in all shapes and sizes and when you choose one, you need to consider its head weight (usually between 16 and 20 ounces), the length of the handle, the shape of the grip, etc. Appropriate specifications for particular hammering tasks have been calculated in great detail. The data on which these specifications is based on an analysis of the hand size and upper body strength of the typical user. The typical user is a man, and the typical hammer has been designed for a man. The average male hand length is 177.9 mm, that of the average woman is 10 mm shorter (Wang & Cai, 2017). Women typically have about half the upper body strength of men (Miller et al., 1993). It’s possible, but not easy to find hammers designed for women (they are referred to as ‘Ladies hammers’ on Amazon). They have a much lighter head weight, a shorter handle length, and many come in pink or floral designs. Hammers, in other words, are far from neutral: they are highly gendered. Ventilla was an impressive money-raiser who used, and appeared to believe, every cliché in the edTech sales manual. Dressed in regulation jeans, polo shirt and fleece, he claimed that schools in America were ‘

Ventilla was an impressive money-raiser who used, and appeared to believe, every cliché in the edTech sales manual. Dressed in regulation jeans, polo shirt and fleece, he claimed that schools in America were ‘ My first question was: how do conference presenters feel about personalised learning? One way of finding out is by looking at the adjectives that are found in close proximity. This is what you get.

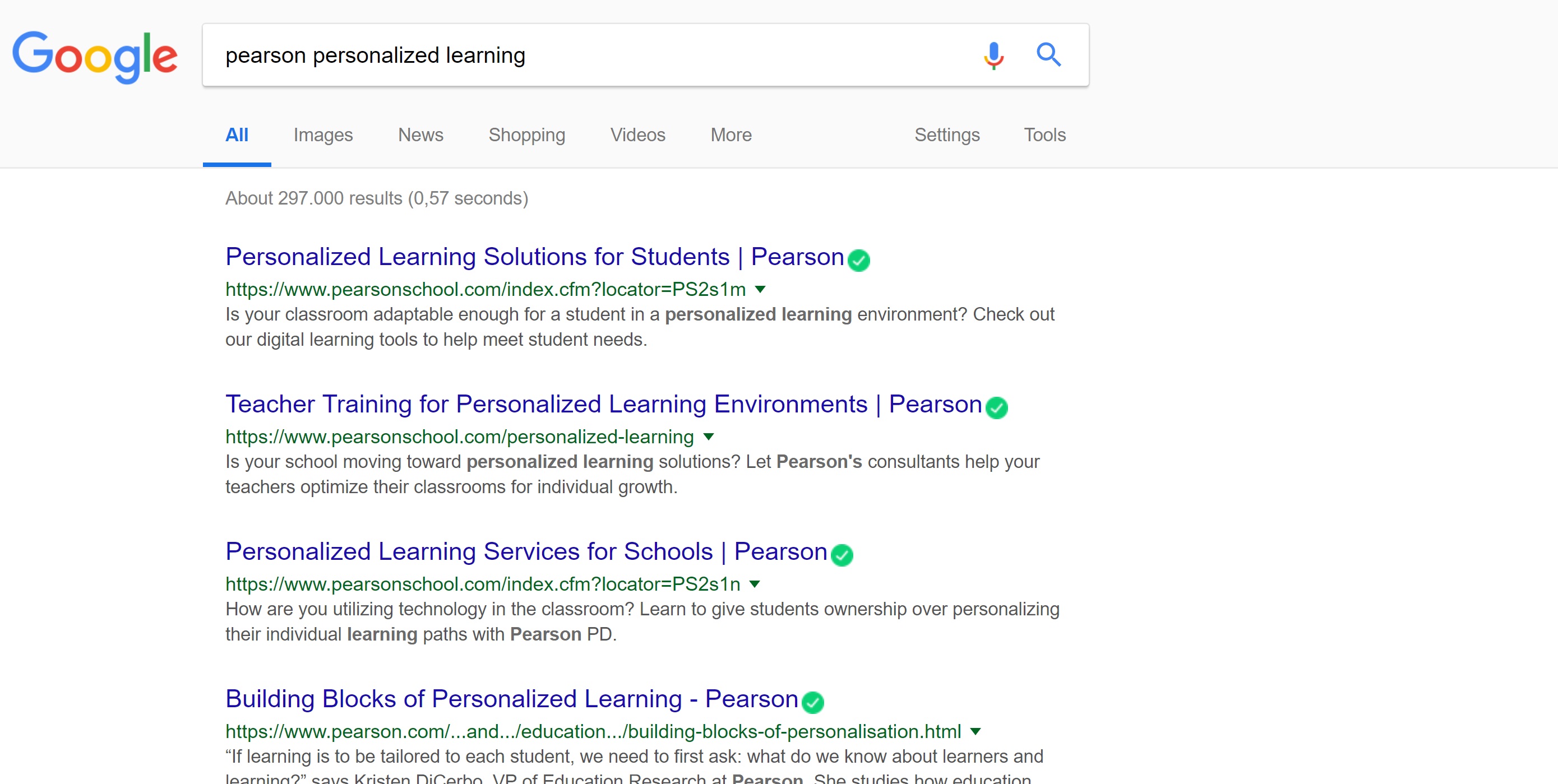

My first question was: how do conference presenters feel about personalised learning? One way of finding out is by looking at the adjectives that are found in close proximity. This is what you get. One of the most significant players in this field is Pearson, who have long been one of the most visible promoters of personalized learning (see the screen capture). At IATEFL, two of the ten conference abstracts which include the word ‘personalized’ are directly sponsored by Pearson. Pearson actually have ten presentations they have directly sponsored or are very closely associated with. Many of these do not refer to personalized learning in the abstract, but would presumably do so in the presentations themselves. There is, for example, a report on a professional development programme in Brazil using TDI (see above). There are two talks about the GSE, described as a tool ‘used to provide a personalised view of students’ language’. The marketing intent is clear: Pearson is to be associated with personalized learning (which is, in turn, associated with a variety of tech tools) – they even have a VP of data analytics, data science and personalized learning.

One of the most significant players in this field is Pearson, who have long been one of the most visible promoters of personalized learning (see the screen capture). At IATEFL, two of the ten conference abstracts which include the word ‘personalized’ are directly sponsored by Pearson. Pearson actually have ten presentations they have directly sponsored or are very closely associated with. Many of these do not refer to personalized learning in the abstract, but would presumably do so in the presentations themselves. There is, for example, a report on a professional development programme in Brazil using TDI (see above). There are two talks about the GSE, described as a tool ‘used to provide a personalised view of students’ language’. The marketing intent is clear: Pearson is to be associated with personalized learning (which is, in turn, associated with a variety of tech tools) – they even have a VP of data analytics, data science and personalized learning. It is also a marvellous example of propaganda, of the way that consent is manufactured. (If you haven’t read it yet, it’s probably time to read Herman and Chomsky’s ‘Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media’.) An excellent account of the way that consent for personalized learning has been manufactured can be found at

It is also a marvellous example of propaganda, of the way that consent is manufactured. (If you haven’t read it yet, it’s probably time to read Herman and Chomsky’s ‘Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media’.) An excellent account of the way that consent for personalized learning has been manufactured can be found at

I also tried to have a conversation with

I also tried to have a conversation with  And a few months ago Duolingo began incorporating bots. These are currently only available for French, Spanish and German learners in the iPhone app, so I haven’t been able to try it out and evaluate it. According to an

And a few months ago Duolingo began incorporating bots. These are currently only available for French, Spanish and German learners in the iPhone app, so I haven’t been able to try it out and evaluate it. According to an