I have been putting in a lot of time studying German vocabulary with Memrise lately, but this is not a review of the Memrise app. For that, I recommend you read Marek Kiczkowiak’s second post on this app. Like me, he’s largely positive, although I am less enthusiastic about Memrise’s USP, the use of mnemonics. It’s not that mnemonics don’t work – there’s a lot of evidence that they do: it’s just that there is little or no evidence that they’re worth the investment of time.

Time … as I say, I have been putting in the hours. Every day, for over a month, averaging a couple of hours a day, it’s enough to get me very near the top of the leader board (which I keep a very close eye on) and it means that I am doing more work than 99% of other users. And, yes, my German is improving.

Putting in the time is the sine qua non of any language learning and a well-designed app must motivate users to do this. Relevant content will be crucial, as will satisfactory design, both visual and interactive. But here I’d like to focus on the two other key elements: task design / variety and gamification.

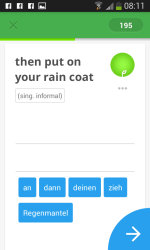

Memrise offers a limited range of task types: presentation cards (with word, phrase or sentence with translation and audio recording), multiple choice (target item with four choices), unscrambling letters or words, and dictation (see below).

As Marek writes, it does get a bit repetitive after a while (although less so than thumbing through a pack of cardboard flashcards). The real problem, though, is that there are only so many things an app designer can do with standard flashcards, if they are to contribute to learning. True, there could be a few more game-like tasks (as with Quizlet), races against the clock as you pop word balloons or something of the sort, but, while these might, just might, help with motivation, these games rarely, if ever, contribute much to learning.

What’s more, you’ll get fed up with the games sooner or later if you’re putting in serious study hours. Even if Memrise were to double the number of activity types, I’d have got bored with them by now, in the same way I got bored with the Quizlet games. Bear in mind, too, that I’ve only done a month: I have at least another two months to go before I finish the level I’m working on. There’s another issue with ‘fun’ activities / games which I’ll come on to later.

The options for task variety in vocabulary / memory apps are therefore limited. Let’s look at gamification. Memrise has leader boards (weekly, monthly, ‘all time’), streak badges, daily goals, email reminders and (in the laptop and premium versions) a variety of graphs that allow you to analyse your study patterns. Your degree of mastery of learning items is represented by a growing flower that grows leaves, flowers and withers. None of this is especially original or different from similar apps.

The trouble with all of this is that it can only work for a certain time and, for some people, never. There’s always going to be someone like me who can put in a couple of hours a day more than you can. Or someone, in my case, like ‘Nguyenduyha’, who must be doing about four hours a day, and who, I know, is out of my league. I can’t compete and the realisation slowly dawns that my life would be immeasurably sadder if I tried to.

The trouble with all of this is that it can only work for a certain time and, for some people, never. There’s always going to be someone like me who can put in a couple of hours a day more than you can. Or someone, in my case, like ‘Nguyenduyha’, who must be doing about four hours a day, and who, I know, is out of my league. I can’t compete and the realisation slowly dawns that my life would be immeasurably sadder if I tried to.

Having said that, I have tried to compete and the way to do so is by putting in the time on the ‘speed review’. This is the closest that Memrise comes to a game. One hundred items are flashed up with four multiple choices and these are against the clock. The quicker you are, the more points you get, and if you’re too slow, or you make a mistake, you lose a life. That’s how you gain lots of points with Memrise. The problem is that, at best, this task only promotes receptive knowledge of the items, which is not what I need by this stage. At worst, it serves no useful learning function at all because I have learnt ways of doing this well which do not really involve me processing meaning at all. As Marek says in his post (in reference to Quizlet), ‘I had the feeling that sometimes I was paying more attention to ‘winning’ the game and scoring points, rather than to the words on the screen.’ In my case, it is not just a feeling: it’s an absolute certainty.

Sadly, the gamification is working against me. The more time I spend on the U-Bahn doing Memrise, the less time I spend reading the free German-language newspapers, the less time I spend eavesdropping on conversations. Two hours a day is all I have time for for my German study, and Memrise is eating it all up. I know that there are other, and better, ways of learning. In order to do what I know I should be doing, I need to ignore the gamification. For those, more reasonable, students, who can regularly do their fifteen minutes a day, day in – day out, the points and leader boards serve no real function at all.

Cheating at gamification, or gaming the system, is common in app-land. A few years ago, Memrise had to take down their leader board when they realised that cheating was taking place. There’s an inexorable logic to this: gamification is an attempt to motivate by rewarding through points, rather than the reward coming from the learning experience. The logic of the game overtakes itself. Is ‘Nguyenduyha’ cheating, or do they simply have nothing else to do all day? Am I cheating by finding time to do pointless ‘speed reviews’ that earn me lots of points?

For users like myself, then, gamification design needs to be a delicate balancing act. For others, it may be largely an irrelevance. I’ve been working recently on a general model of vocabulary app design that looks at two very different kinds of user. On the one hand, there are the self-motivated learners like myself or the millions of other who have chosen to use self-study apps. On the other, there are the millions of students in schools and colleges, studying English among other subjects, some of whom are now being told to use the vocabulary apps that are beginning to appear packaged with their coursebooks (or other learning material). We’ve never found entirely satisfactory ways of making these students do their homework, and the fact that this homework is now digital will change nothing (except, perhaps, in the very, very short term). The incorporation of games and gamification is unlikely to change much either: there will always be something more interesting and motivating (and unconnected with language learning) elsewhere.

Teachers and college principals may like the idea of gamification (without having really experienced it themselves) for their students. But more important for most of them is likely to be the teacher dashboard: the means by which they can check that their students are putting the time in. Likewise, they will see the utility of automated email reminders that a student is not working hard enough to meet their learning objectives, more and more regular tests that contribute to overall course evaluation, comparisons with college, regional or national benchmarks. Technology won’t solve the motivation issue, but it does offer efficient means of control.

Thanks for this Philip, your analysis underscores for me something I have been wrestling with for the past couple of years.

I am a bit of a tech weenie and love to try new language learning apps and software. However, I always walk away from the experience questioning the experience. I guess I should know better by now, that there is never a one size fits all solution.

An excellent and well thought through article.Thanks for sharing.

Hi Philip,

Some great points here. You’re right that no matter how many games there might be in an app, you’d still get bored of them. And as you say, the question is: would a game-like format contribute more to learning? Perhaps to increasing motivation with certain learners, yes. But I doubt if you’d learn more. For example, I hardly ever use the speed review on Memrise, because I feel I don’t get enough time to consciously recall the word, and maybe even say it out loud before I choose the correct option or type it in. After doing a whole round of speed review, I don’t really get a feeling that I’ve revised the words at all.

When it comes to the mnemonics, for some reason Memrise got rid of the image search engine that was there when you clicked on creating a new meme. This meant that it took two seconds to find a good pic and then add a funny line to it. Now you have to go to google, find the pic, download, and then upload to Memrise. I stopped adding pictures myself to the mnemonics. Can’t be asked any more. I thought it was really nicely set up before and I’m not sure why they got rid of it. Still think adding a funny sentence (without a pic) helps remember the word. And doesn’t take long. I won’t do it for all the words, though. Just some.

What do you think of the spaced-repetition system? For me that’s one of the strongest parts of the app and the website.

Have you seen my recent videos on YouTube about Memrise?

1. How to create a course for your learners: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dm1g6nclwqw

2. Some features that make Memrise a really useful language learning tool: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ydtUfoT92lY

Thanks, Marek, for the links. Useful, practical videos.

In answer to your question about the spaced repetition, I find it very hard to compare one system with another. I’m happy enough with Memrise on this score, and I can’t say much more than that!

You’re welcome. Glad you liked them.

Re spaced repetition, I’m just wondering how scientific it is. To me it makes a lot of sense and seems to be working very well, but wondering if there’s any memory research behind it. I’ve read about memory curve and the time intervals for revision, but it was in a magazine. Do you know if anyone has done research on it, especially as far as SLA and vocab are concerned?

There are so many variables, Marek, besides the algorithms (especially since a research project has to take place over a long time span), that it’s a difficult area to research. Much of it seems to have been done with invented words, rather than real languages, and there’s nothing I know that I’d recommend.

However, as we’re on the subject of research, you might find this extract from Joe Barcroft’s book (‘Lexical Input Processing and Vocabulary Learning’, p.81) interesting. It’s on the topic of mnemonics:

Studies on the Keyword Method have demonstrated that groups learning with Keyword often obtain higher vocabulary learning scores as compared to alternative unconstrained or self-selected strategy groups (e.g. Atkinson & Raugh, 1975; Ellis & Beaton, 1993; Sagarra & Alba, 2006). Brown and Perry (1991) also concluded that learners using Keyword who also were presented with definitions and examples of words in sentences (Keyword-Semantic) learned significantly more vocabulary than learners using Keyword alone. Other research, however, has demonstrated that L2 words learned via Keyword can be more prone to long-term forgetting as compared to a non-mnemonic technique such as rote rehearsal (Wang & Thomas, 1995) or result in worse performance than rote rehearsal in some contexts (e.g., Van Hell & Mahn, 1997). In addition, from the perspective of the quality of the semantic representation of each developing L2 word, it turns out that the Keyword Method can be problematic. Barcroft, Sommers and Sunderman (2011) found that the introduction of Keyword primes during a translation task, which were similar in form to the L2 words, speeded recall for a group who had studied vocabulary via rote rehearsal but slowed recall for a group who had studied the same vocabulary using the Keyword Method (see also Kole, 2007; van Hell and Mahn, 1997).

Great stuff, Philip.

Interestingly, in the latest issue of Language Teaching (April 2016), there is a review of research into gifted language learners (also known as hyperpolyglots), where, unsurprisingly perhaps, memory and memorisation plays an important role: ‘The extraordinary memory abilities of gifted L2 learners reported in research confirm Skehan’s (1998) assumption that the most significant characteristic of exceptionally successful learners is unusual verbal memory’ (p. 170). However the writers add that it is not clear yet as to whether these memory abilities are innate or ‘rather, evolve as a result of multiple experiences of FL learning. Probably the two possibilities are not mutually exclusive.’

It does seem that hyperpolyglots are ‘masters of learning strategies’, such as collecting and using dictionaries, reference grammars and so on. Also, ‘hyperpolyglots read a lot. They rely on all the possible types of techniques to enhance their learning, such as playing games, singing, visualising, talking to themselves, seeking error correction, finding rules and patterns, using recordings to learn sounds and words, following structured reviews, or inventing mnemonic devices. The most prominent among the numerous strategies used by hyperpolyglots are memory strategies. They usually involve repeating patterns many times so that they become internalised, automatic and accessible with little cognitive effort’ (p 175).

They also put in a great deal of time – ‘they spend many hours a day practising the languages they learn, which might involve performing memory exercises, translating, writing and reading practice, doing grammar exercises and all possible sorts of revisions’. But the important point is that their motivation to do this is almost entirely intrinsic: ‘They gain expertise not because they work hard but mainly because they find working hard rewarding’.

By stimulating an endorphin rush in learners who are not so intrinsically motivated, gamification goes some way towards making hard work seem rewarding. But, like most artificial stimulants, it is subject to the law of diminishing returns. And the rewards, as you point out, may be tangential to the real goal.

Reference:

Biedroń, A. and Pawlak, M. (2016). ‘New conceptualisations of linguistic giftedness.’ Language Teaching, 49, 2.

Thanks, Scott. That volume is still lying unread on the shelf – it’s time I opened it.

Such an interesting post and comment on gamification. It is something I’ve been thinking a lot about, too many teachers and schools have been sold that gamification is the sole answer to all their students motivation problems but as you’ve clearly pointed out it doesn’t always work as intended. Thank you for another well thought out post.

[…] Vocabulary apps – time and motivation […]