As both a language learner and a teacher, I have a number of questions about the value of watching subtitled videos for language learning. My interest is in watching extended videos, rather than short clips for classroom use, so I am concerned with incidental, rather than intentional, learning, mostly of vocabulary. My questions include:

As both a language learner and a teacher, I have a number of questions about the value of watching subtitled videos for language learning. My interest is in watching extended videos, rather than short clips for classroom use, so I am concerned with incidental, rather than intentional, learning, mostly of vocabulary. My questions include:

- Is it better to watch a video that is subtitled or unsubtitled?

- Is it better to watch a video with L1 or L2 subtitles?

- If a video is watched more than once, what is the best way to start and proceed? In which order (no subtitles, L1 subtitles and L2 subtitles) is it best to watch?

For help, I turned to three recent books about video and language learning: Ben Goldstein and Paul Driver’s Language Learning with Digital Video (CUP, 2015), Kieran Donaghy’s Film in Action (Delta, 2015) and Jamie Keddie’s Bringing Online Video into the Classroom (OUP, 2014). I was surprised to find no advice, but, as I explored more, I discovered that there may be a good reason for these authors’ silence.

There is now a huge literature out there on subtitles and language learning, and I cannot claim to have read it all. But I think I have read enough to understand that I am not going to find clear-cut answers to my questions.

The learning value of subtitles

It has been known for some time that the use of subtitles during extensive viewing of video in another language can help in the acquisition of that language. The main gains are in vocabulary acquisition and the development of listening skills (Montero Perez et al., 2013). This is true of both L1 subtitles (with an L2 audio track), sometimes called interlingual subtitles, (Incalcaterra McLoughlin et al, 2011) and L2 subtitles (with an L2 audio track), sometimes called intralingual subtitles or captions (Vanderplank, 1988). Somewhat more surprisingly, vocabulary gains may also come from what are called reversed subtitles (L2 subtitles and an L1 audio track) (Burczyńska, 2015). Of course, certain conditions apply for subtitled video to be beneficial, and I’ll come on to these. But there is general research agreement (an exception is Karakaş & Sariçoban, 2012) that more learning is likely to take place from watching a subtitled video in a target language than an unsubtitled one.

Opposition to the use of subtitles as a tool for language learning has mostly come from three angles. The first of these, which concerns L1 subtitles, is an antipathy to any use at all of L1. Although such an attitude remains entrenched in some quarters, there is no evidence to support it (Hall & Cook, 2012; Kerr, 2016). Researchers and, increasingly, teachers have moved on.

The second reservation that is sometimes expressed is that learners may not attend to either the audio track or the subtitles if they do not need to. They may, for example, ignore the subtitles in the case of reversed subtitles or ignore the L2 audio track when there are L1 subtitles. This can, of course, happen, but it seems that, on the whole, this is not the case. In an eye-tracking study by Bisson et al (2012), for example, it was found that most people followed the subtitles, irrespective of what kind they were. Unsurprisingly, they followed the subtitles more closely when the audio track was in a language that was less familiar. When conditions are right (see below), reading subtitles becomes a very efficient and partly automatized cognitive activity, which does not prevent people from processing the audio track at the same time (d’Ydewalle & Pavakanun, 1997).

Related to the second reservation is the concern that the two sources of information (audio and subtitles), combined with other information (images and music or sound effects), may be in competition and lead to cognitive overload, impacting negatively on both comprehension and learning. Recent research suggests that this concern is ungrounded (Kruger et al, 2014). L1 subtitles generate less cognitive load than L2 subtitles, but overload is not normally reached and mental resources are still available for learning (Baranowska, 2020). The absence of subtitles generates more cognitive load.

Conditions for learning

Before looking at the differences between L1 and L2 subtitles, it’s a good idea to look at the conditions under which learning is more likely to take place with subtitles. Some of these are obvious, others less so.

First of all, the video material must be of sufficient intrinsic interest to the learner. Secondly, the subtitles must be of a sufficiently high quality. This is not always the case with automatically generated captions, especially if the speech-to-text software struggles with the audio accent. It is also not always the case with professionally produced L1 subtitles, especially when the ‘translations are non-literal and made at the phrase level, making it hard to find connections between the subtitle text and the words in the video’ (Kovacs, 2013, cited by Zabalbeascoa et al., 2015: 112). As a minimum, standard subtitling guidelines, such as those produced for the British Channel 4, should be followed. These limit, for example, the number of characters per line to about 40 and a maximum of two lines.

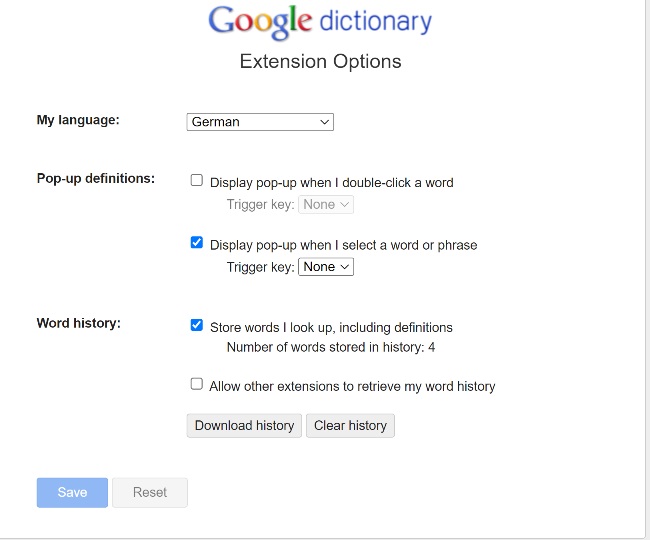

For reasons that I’ll come on to, learners should be able to switch easily between L1 and L2 subtitles. They are also likely to benefit if reliably accurate glosses or hyperlinks are ‘embedded in the subtitles, making it possible for a learner to simply click for additional verbal, auditory or even pictorial glosses’ (Danan, 2015: 49).

At least as important as considerations of the materials or tools, is a consideration of what the learner brings to the activity (Frumuselu, 2019: 104). Vanderplank (2015) describes these different kinds of considerations as the ‘effects of’ subtitles on a learner and the ‘effects with’ subtitles on learner behaviour.

In order to learn from subtitles, you need to be able to read fast enough to process them. Anyone with a slow reading speed (e.g. some dyslexics) in their own language is going to struggle. Even with L1 subtitles, Vanderplank (2015: 24) estimates that it is only around the age of 10 that children can do this with confidence. Familarity with both the subject matter and with subtitle use will impact on this ability to read subtitles fast enough.

With L2 subtitles, the language proficiency of the learner related to the level of difficulty (especially lexical difficulty) of the subtitles will clearly be of some significance. It is unlikely that L2 subtitles will be of much benefit to beginners (Taylor, 2005). It also suggests that, at lower levels, materials need to be chosen carefully. On the whole, researchers have found that higher proficiency levels correlate with greater learning gains (Pujadas & Muñoz, 2019; Suárez & Gesa, 2019), but one earlier meta-analysis (Montero Perez et al., 2013) did not find that proficiency levels were significant.

Measures of general language proficiency may be too blunt an instrument to help us all of the time. I can learn more from Portuguese than from Arabic subtitles, even though I am a beginner in both languages. The degree of proximity between two languages, especially the script (Winke et al., 2010), is also likely to be significant.

But a wide range of other individual learner differences will also impact on the learning from subtitles. It is known that learners approach subtitles in varied and idiosyncratic ways (Pujolá, 2002), with some using L2 subtitles only as a ‘back-up’ and others relying on them more. Vanderplank (2019) grouped learners into three broad categories: minimal users who were focused throughout on enjoying films as they would in their L1, evolving users who showed marked changes in their viewing behaviour over time, and maximal users who tended to be experienced at using films to enhance their language learning.

Categories like these are only the tip of the iceberg. Sensory preferences, personality types, types of motivation, the impact of subtitles on anxiety levels and metacognitive strategy awareness are all likely to be important. For the last of these, Danan (2015: 47) asks whether learners should be taught ‘techniques to make better use of subtitles and compensate for weaknesses: techniques such as a quick reading of subtitles before listening, confirmation of word recognition or meaning after listening, as well as focus on form for spelling or grammatical accuracy?’

In short, it is, in practice, virtually impossible to determine optimal conditions for learning from subtitles, because we cannot ‘take into account all the psycho-social, cultural and pedagogic parameters’ (Gambier, 2015). With that said, it’s time to take a closer look at the different potential of L1 and L2 subtitles.

L1 vs L2 subtitles

Since all other things are almost never equal, it is not possible to say that one kind of subtitles offers greater potential for learning than another. As regards gains in vocabulary acquisition and listening comprehension, there is no research consensus (Baranowska, 2020: 107). Research does, however, offer us a number of pointers.

Extensive viewing of subtitled video (both L1 and L2) can offer ‘massive quantities of authentic and comprehensible input’ (Vanderplank, 1988: 273). With lower level learners, the input is likely to be more comprehensible with L1 subtitles, and, therefore, more enjoyable and motivating. This makes them often more suitable for what Caimi (2015: 11) calls ‘leisure viewing’. Vocabulary acquisition may be better served with L2 subtitles, because they can help viewers to recognize the words that are being spoken, increase their interaction with the target language, provide further language context, and increase the redundancy of information, thereby enhancing the possibility of this input being stored in long-term memory (Frumuselu et al., 2015). These effects are much more likely with Vanderplank’s (2019) motivated, ‘maximal’ users than with ‘minimal’ users.

There is one further area where L2 subtitles may have the edge over L1. One of the values of extended listening in a target language is the improvement in phonetic retuning (see, for example, Reinisch & Holt, 2013), the ability to adjust the phonetic boundaries in your own language to the boundaries that exist in the target language. Learning how to interpret unusual speech-sounds, learning how to deal with unusual mappings between sounds and words and learning how to deal with the acoustic variations of different speakers of the target language are all important parts of acquiring another language. Research by Mitterer and McQueen (2009) suggests that L2 subtitles help in this process, but L1 subtitles hinder it.

Classroom implications?

The literature on subtitles and language learning echoes with the refrain of ‘more research needed’, but I’m not sure that further research will lead to less ambiguous, practical conclusions. One of my initial questions concerned the optimal order of use of different kinds of subtitles. In most extensive viewing contexts, learners are unlikely to watch something more than twice. If they do (watching a recorded academic lecture, for example), they are likely to be more motivated by a desire to learn from the content than to learn language from the content. L1 subtitles will probably be preferred, and will have the added bonus of facilitating note-taking in the L1. For learners who are more motivated to learn the target language (Vanderplank’s ‘maximal’ users), a sequence of subtitle use, starting with the least cognitively challenging and moving to greater challenge, probably makes sense. Danan (2015: 46) suggests starting with an L1 soundtrack and reversed (L2) subtitles, then moving on to an L2 soundtrack and L2 subtitles, and ending with an L2 soundtrack and no subtitles. I would replace her first stage with an L2 soundtrack and L1 subtitles, but this is based on hunch rather than research.

This sequencing of subtitle use is common practice in language classrooms, but, here, (1) the video clips are usually short, and (2) the aim is often not incidental learning of vocabulary. Typically, the video clip has been selected as a tool for deliberate teaching of language items, so different conditions apply. At least one study has confirmed the value of the common teaching practice of pre-teaching target vocabulary items before viewing (Pujadas & Muñoz, 2019). The drawback is that, by getting learners to focus on particular items, less incidental learning of other language features is likely to take place. Perhaps this doesn’t matter too much. In a short clip of a few minutes, the opportunities for incidental learning are limited, anyway. With short clips and a deliberate learning aim, it seems reasonable to use L2 subtitles for a first viewing, and no subtitles thereafter.

An alternative frequent use of short video clips in classrooms is to use them as a springboard for speaking. In these cases, Baranowska (2020: 113) suggests that teachers may opt for L1 subtitles first, and follow up with L2 subtitles. Of course, with personal viewing devices or in online classes, teachers may want to exploit the possibilities of differentiating the subtitle condition for different learners.

REFERENCES

Baranowska, K. (2020). Learning most with least effort: subtitles and cognitive load. ELT Journal 74 (2): pp.105 – 115

Bisson, M.-J., Van Heuven, W.J.B., Conklin, K. and Tunney, R.J. (2012). Processing of native and foreign language subtitles in films: An eye tracking study. Applied Psycholingistics, 35 (2): pp. 399 – 418

Burczyńska, P. (2015). Reversed Subtitles as a Powerful Didactic Tool in SLA. In Gambier, Y., Caimi, A. & Mariotti, C. (Eds.), Subtitles and Language Learning. Principles, strategies and practical experiences. Bern: Peter Lang (pp. 221 – 244)

Caimi, A. (2015). Introduction. In Gambier, Y., Caimi, A. & Mariotti, C. (Eds.), Subtitles and Language Learning. Principles, strategies and practical experiences. Bern: Peter Lang (pp. 9 – 18)

Danan, M. (2015). Subtitling as a Language Learning Tool: Past Findings, Current Applications, and Future Paths. In Gambier, Y., Caimi, A. & Mariotti, C. (Eds.), Subtitles and Language Learning. Principles, strategies and practical experiences. Bern: Peter Lang (pp. 41 – 61)

d’Ydewalle, G. & Pavakanun, U. (1997). Could Enjoying a Movie Lead to Language Acquisition?. In: Winterhoff-Spurk, P., van der Voort, T.H.A. (Eds.) New Horizons in Media Psychology. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-10899-3_10

Frumuselu, A.D., de Maeyer, S., Donche, V. & Gutierrez Colon Plana, M. (2015). Television series inside the EFL classroom: bridging the gap between teaching and learning informal language through subtitles. Linguistics and Education, 32: pp. 107 – 17

Frumuselu, A. D. (2019). ‘A Friend in Need is a Film Indeed’: Teaching Colloquial Expressions with Subtitled Television Series. In Herrero, C. & Vanderschelden, I. (Eds.) Using Film and Media in the Language Classroom. Bristol: Multimedia Matters. pp.92 – 107

Gambier, Y. (2015). Subtitles and Language Learning (SLL): Theoretical background. In Gambier, Y., Caimi, A. & Mariotti, C. (Eds.), Subtitles and Language Learning. Principles, strategies and practical experiences. Bern: Peter Lang (pp. 63 – 82)

Hall, G. & Cook, G. (2012). Own-language Use in Language Teaching and Learning. Language Learning, 45 (3): pp. 271 – 308

Incalcaterra McLoughlin, L., Biscio, M. & Ní Mhainnín, M. A. (Eds.) (2011). Audiovisual Translation, Subtitles and Subtitling. Theory and Practice. Bern: Peter Lang

Karakaş, A. & Sariçoban, A. (2012). The impact of watching subtitled animated cartoons on incidental vocabulary learning of ELT students. Teaching English with Technology, 12 (4): pp. 3 – 15

Kerr, P. (2016). Questioning ‘English-only’ Classrooms: Own-language Use in ELT. In Hall, G. (Ed.) The Routledge Handbook of English Language Teaching (pp. 513 – 526)

Kruger, J. L., Hefer, E. & Matthew, G. (2014). Attention distribution and cognitive load in a subtitled academic lecture: L1 vs. L2. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 7: pp. 1 – 15

Mitterer, H. & McQueen, J. M. (2009). Foreign Subtitles Help but Native-Language Subtitles Harm Foreign Speech Perception. PLoS ONE 4 (11): e7785.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007785

Montero Perez, M., Van Den Noortgate, W., & Desmet, P. (2013). Captioned video for L2 listening and vocabulary learning: A meta-analysis. System, 41, pp. 720–739 doi:10.1016/j.system.2013.07.013

Pujadas, G. & Muñoz, C. (2019). Extensive viewing of captioned and subtitled TV series: a study of L2 vocabulary learning by adolescents, The Language Learning Journal, 47:4, 479-496, DOI: 10.1080/09571736.2019.1616806

Pujolá, J.- T. (2002). CALLing for help: Researching language learning strategies using help facilities in a web-based multimedia program. ReCALL, 14 (2): pp. 235 – 262

Reinisch, E. & Holt, L. L. (2013). Lexically Guided Phonetic Retuning of Foreign-Accented Speech and Its Generalization. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0034409

Suárez, M. & Gesa, F. (2019) Learning vocabulary with the support of sustained exposure to captioned video: do proficiency and aptitude make a difference? The Language Learning Journal, 47:4, 497-517, DOI: 10.1080/09571736.2019.1617768

Taylor, G. (2005). Perceived processing strategies of students watching captioned video. Foreign Language Annals, 38(3), pp. 422-427

Vanderplank, R. (1988). The value of teletext subtitles in language learning. ELT Journal, 42 (4): pp. 272 – 281

Vanderplank, R. (2015). Thirty Years of Research into Captions / Same Language Subtitles and Second / Foreign Language Learning: Distinguishing between ‘Effects of’ Subtitles and ‘Effects with’ Subtitles for Future Research. In Gambier, Y., Caimi, A. & Mariotti, C. (Eds.), Subtitles and Language Learning. Principles, strategies and practical experiences. Bern: Peter Lang (pp. 19 – 40)

Vanderplank, R. (2019). ‘Gist watching can only take you so far’: attitudes, strategies and changes in behaviour in watching films with captions, The Language Learning Journal, 47:4, 407-423, DOI: 10.1080/09571736.2019.1610033

Winke, P., Gass, S. M., & Sydorenko, T. (2010). The Effects of Captioning Videos Used for Foreign Language Listening Activities. Language Learning & Technology, 1 (1): pp. 66 – 87

Zabalbeascoa, P., González-Casillas, S. & Pascual-Herce, R. (2015). In Gambier, Y., Caimi, A. & Mariotti, C. (Eds.), Subtitles and Language Learning. Principles, strategies and practical experiences Bern: Peter Lang (pp. 105–126)

As both a language learner and a teacher, I have a number of questions about the value of watching subtitled videos for language learning. My interest is in watching extended videos, rather than short clips for classroom use, so I am concerned with incidental, rather than intentional, learning, mostly of vocabulary. My questions include:

As both a language learner and a teacher, I have a number of questions about the value of watching subtitled videos for language learning. My interest is in watching extended videos, rather than short clips for classroom use, so I am concerned with incidental, rather than intentional, learning, mostly of vocabulary. My questions include:

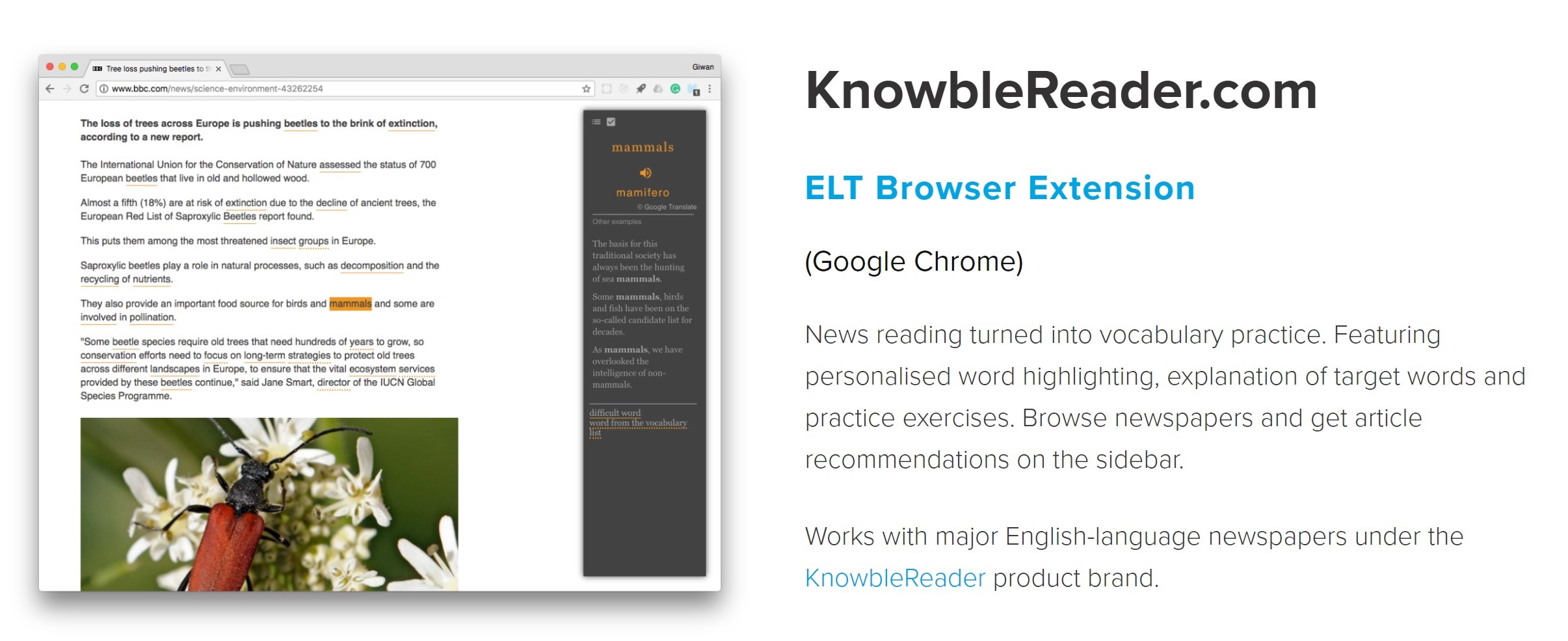

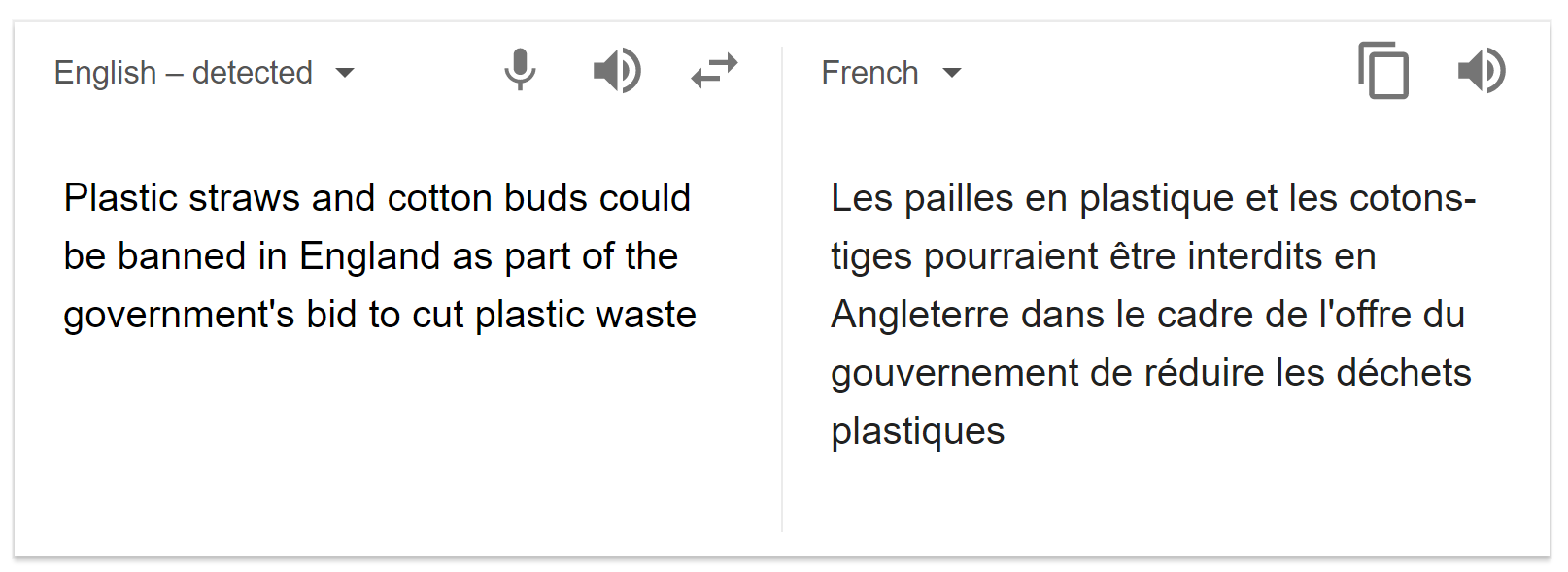

One of the reasons that Google Translate has improved is that it no longer treats individual words as individual lexical items. It analyses groups of words and translates chunks or phrases (see, for example, the way it translates ‘as part of’). It doesn’t do word-for-word translation. Knowble, however, have set their software to ask Google for translations of each word as individual items, so the phrase ‘as part of’ is translated ‘comme’ + ‘partie’ + ‘de’. Whilst this example is comprehensible, problems arise very quickly. ‘Cotton buds’ (‘cotons-tiges’) become ‘coton’ + ‘bourgeon’ (= botanical shoots of cotton). Phrases like ‘in time’, ‘run into’, ‘sleep it off’ ‘take its course’, ‘fire station’ or ‘going on’ (all from the stoned raccoon text) all cause problems. In addition, Knowble are not using any parsing tools, so the system does not identify parts of speech, and further translation errors inevitably appear. In the short article of 240 words, about 10% are wrongly translated. Knowble claim to be using NLP tools, but there’s no sign of it here. They’re just using Google Translate rather badly.

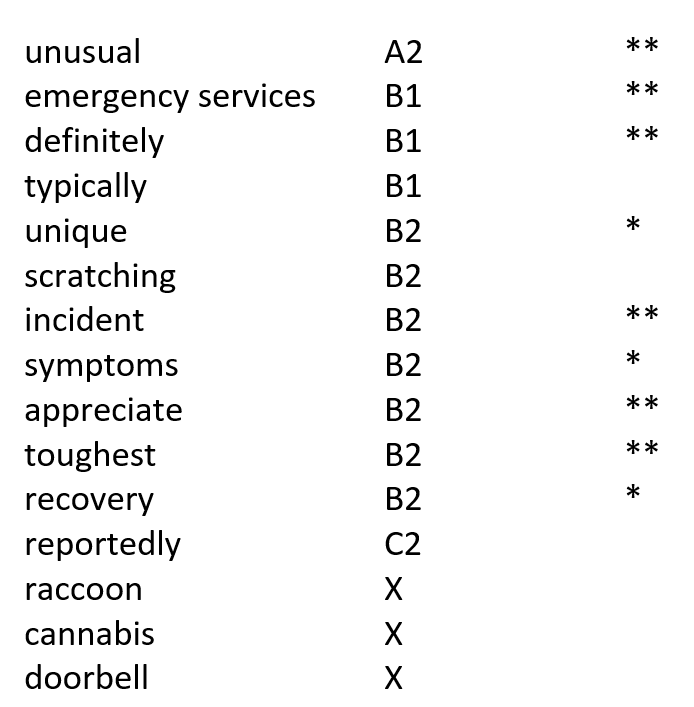

One of the reasons that Google Translate has improved is that it no longer treats individual words as individual lexical items. It analyses groups of words and translates chunks or phrases (see, for example, the way it translates ‘as part of’). It doesn’t do word-for-word translation. Knowble, however, have set their software to ask Google for translations of each word as individual items, so the phrase ‘as part of’ is translated ‘comme’ + ‘partie’ + ‘de’. Whilst this example is comprehensible, problems arise very quickly. ‘Cotton buds’ (‘cotons-tiges’) become ‘coton’ + ‘bourgeon’ (= botanical shoots of cotton). Phrases like ‘in time’, ‘run into’, ‘sleep it off’ ‘take its course’, ‘fire station’ or ‘going on’ (all from the stoned raccoon text) all cause problems. In addition, Knowble are not using any parsing tools, so the system does not identify parts of speech, and further translation errors inevitably appear. In the short article of 240 words, about 10% are wrongly translated. Knowble claim to be using NLP tools, but there’s no sign of it here. They’re just using Google Translate rather badly. NLP tools of some kind are presumably being used to select the words that get underlined. Exactly how this works is unclear. On the whole, it seems that very high frequency words are ignored and that lower frequency words are underlined. Here, for example, is the list of words that were underlined in the stoned raccoon text. I’ve compared them with (1) the CEFR levels for these words in the English Profile Text Inspector, and (2) the frequency information from the Macmillan dictionary (more stars = more frequent). In the other articles, some extremely high frequency words were underlined (e.g. price, cost, year) while much lower frequency items were not.

NLP tools of some kind are presumably being used to select the words that get underlined. Exactly how this works is unclear. On the whole, it seems that very high frequency words are ignored and that lower frequency words are underlined. Here, for example, is the list of words that were underlined in the stoned raccoon text. I’ve compared them with (1) the CEFR levels for these words in the English Profile Text Inspector, and (2) the frequency information from the Macmillan dictionary (more stars = more frequent). In the other articles, some extremely high frequency words were underlined (e.g. price, cost, year) while much lower frequency items were not. Vocabulary learning

Vocabulary learning The claim that Knowble’s ‘learning effect is proven scientifically’ seems to me to be without any foundation. If there has been any proper research, it’s not signposted anywhere. Sure, reading lots of news articles (with a look-up function – if it works reliably) can only be beneficial for language learners, but they can do that with any decent dictionary running in the background.

The claim that Knowble’s ‘learning effect is proven scientifically’ seems to me to be without any foundation. If there has been any proper research, it’s not signposted anywhere. Sure, reading lots of news articles (with a look-up function – if it works reliably) can only be beneficial for language learners, but they can do that with any decent dictionary running in the background.