Vocab Victor is a very curious vocab app. It’s not a flashcard system, designed to extend vocabulary breadth. Rather it tests the depth of a user’s vocabulary knowledge.

The app’s website refers to the work of Paul Meara (see, for example, Meara, P. 2009. Connected Words. Amsterdam: John Benjamins). Meara explored the ways in which an analysis of the words that we associate with other words can shed light on the organisation of our mental lexicon. Described as ‘gigantic multidimensional cobwebs’ (Aitchison, J. 1987. Words in the Mind. Oxford: Blackwell, p.86), our mental lexicons do not appear to store lexical items in individual slots, but rather they are distributed across networks of associations.

The size of the web (i.e. the number of words, or the level of vocabulary breadth) is important, but equally important is the strength of the connections within the web (or vocabulary depth), as this determines the robustness of vocabulary knowledge. These connections or associations are between different words and concepts and experiences, and they are developed by repeated, meaningful, contextualised exposure to a word. In other words, the connections are firmed up through extensive opportunities to use language.

In word association research, a person is given a prompt word and asked to say the first other word that comes to their mind. For an entertaining example of this process at work, you might enjoy this clip from the comedy show ‘Help’. The research has implications for a wide range of questions, not least second language acquisition. For example, given a particular prompt, native speakers produce a relatively small number of associative responses, and these are reasonably predictable. Learners, on the other hand, typically produce a much greater variety of responses (which might seem surprising, given that they have a smaller vocabulary store to select from).

One way of classifying the different kinds of response is to divide them into two categories: syntagmatic (words that are discoursally connected to the prompt, such as collocations) and paradigmatic (words that are semantically close to the prompt and are the same part of speech). Linguists have noted that learners (both L1 children and L2 learners) show a shift from predominantly syntagmatic responses to more paradigmatic responses as their mental lexicon develops.

The developers of Vocab Victor have set out to build ‘more and stronger associations for the words your students already know, and teaches new words by associating them with existing, known words, helping students acquire native-like word networks. Furthermore, Victor teaches different types of knowledge, including synonyms, “type-of” relationships, collocations, derivations, multiple meanings and form-focused knowledge’. Since we know how important vocabulary depth is, this seems like a pretty sensible learning target.

The app attempts to develop this breadth in two main ways (see below). The ‘core game’ is called ‘Word Strike’ where learners have to pick the word on the arrow which most closely matches the word on the target. The second is called ‘Word Drop’ where a bird holds a word card and the user has to decide if it relates more to one of two other words below. Significantly, they carry out these tasks before any kind of association between form and meaning has been established. The meaning of unknown items can be checked in a monolingual dictionary later. There are a couple of other, less important games that I won’t describe now. The graphics are attractive, if a little juvenile. The whole thing is gamified with levels, leaderboards and so on. It’s free and, presumably, still under development.

The app claims to be for ‘English language learners of all ages [to] develop a more native-like vocabulary’. It also says that it is appropriate for ‘native speaking primary students [to] build and strengthen vocabulary for better test performance and stronger reading skills’, as well as ‘secondary students [to] prepare for the PSAT and SAT’. It was the scope of these claims that first set my alarm bells ringing. How could one app be appropriate for such diverse users? (Spoiler: it can’t, and attempts to make an edtech product suitable for everyone inevitably end up with a product that is suitable for no one.)

Rich, associative lexical networks are the result of successful vocabulary acquisition, but neither Paul Meara nor anyone else in the word association field has, to the best of my knowledge, ever suggested that deliberate study is the way to develop the networks. It is uncontentious to say that vocabulary depth (as shown by associative networks) is best developed through extensive exposure to input – reading and listening.

It is also reasonably uncontentious to say that deliberate study of vocabulary pays greatest dividends in developing vocabulary breadth (not depth), especially at lower levels, with a focus on the top three to eight thousand words in terms of frequency. It may also be useful at higher levels when a learner needs to acquire a limited number of new words for a particular purpose. An example of this would be someone who is going to study in an EMI context and would benefit from rapid learning of the words of the Academic Word List.

The Vocab Victor website says that the app ‘is uniquely focused on intermediate-level vocabulary. The app helps get students beyond this plateau by selecting intermediate-level vocabulary words for your students’. At B1 and B2 levels, learners typically know words that fall between #2500 and #3750 in the frequency tables. At level C2, they know most of the most frequent 5000 items. The less frequent a word is, the less point there is in studying it deliberately.

For deliberate study of vocabulary to serve any useful function, the target language needs to be carefully selected, with a focus on high-frequency items. It makes little sense to study words that will already be very familiar. And it makes no sense to deliberately study apparently random words that are so infrequent (i.e. outside the top 10,000) that it is unlikely they will be encountered again before the deliberate study has been forgotten. Take a look at the examples below and judge for yourself how well chosen the items are.

Vocab Victor appears to focus primarily on semantic fields, as in the example above with ‘smashed’ as a key word. ‘Smashed’, ‘fractured’, ‘shattered’ and ‘cracked’ are all very close in meaning. In order to disambiguate them, it would help learners to see which nouns typically collocate with these words. But they don’t get this with the app – all they get are English-language definitions from Merriam-Webster. What this means is that learners are (1) unlikely to develop a sufficient understanding of target items to allow them to incorporate them into their productive lexicon, and (2) likely to get completely confused with a huge number of similar, low-frequency words (that weren’t really appropriate for deliberate study in the first place). What’s more, lexical sets of this kind may not be a terribly good idea, anyway (see my blog post on the topic).

Vocab Victor takes words, as opposed to lexical items, as the target learning objects. Users may be tested on the associations of any of the meanings of polysemantic items. In the example below (not perhaps the most appropriate choice for primary students!), there are two main meanings, but with other items, things get decidedly more complex (see the example with ‘toss’). Learners are also asked to do the associative tasks ‘Word Strike’ and ‘Word Drop’ before they have had a chance to check the possible meanings of either the prompt item or the associative options.

How anyone could learn from any of this is quite beyond me. I often struggled to choose the correct answer myself; there were also a small number of items whose meaning I wasn’t sure of. I could see no clear way in which items were being recycled (there’s no spaced repetition here). The website claims that ‘adaptating [sic] to your student’s level happens automatically from the very first game’, but I could not see this happening. In fact, it’s very hard to adapt target item selection to an individual learner, since right / wrong or multiple choice answers tell us so little. Does a correct answer tell us that someone knows an item or just that they made a lucky guess? Does an incorrect answer tell us that an item is unknown or just that, under game pressure, someone tapped the wrong button? And how do you evaluate a learner’s lexical level (as a starting point), even with very rough approximation, without testing knowledge of at least thirty items first? All in all, then, a very curious app.

One of the most powerful associative responses to a word (especially with younger learners) is what is called a ‘klang’ response: another word which rhymes with or sounds like the prompt word. So, if someone says the word ‘app’ to you, what’s the first klang response that comes to mind?

Like the mythical monster, the ancient Hydra organisation of Marvel Comics grows two more heads if one is cut off, becoming more powerful in the process. With the most advanced technology on the planet and with a particular focus on data gathering, Hydra operates through international corporations and highly-placed individuals in national governments.

Like the mythical monster, the ancient Hydra organisation of Marvel Comics grows two more heads if one is cut off, becoming more powerful in the process. With the most advanced technology on the planet and with a particular focus on data gathering, Hydra operates through international corporations and highly-placed individuals in national governments.

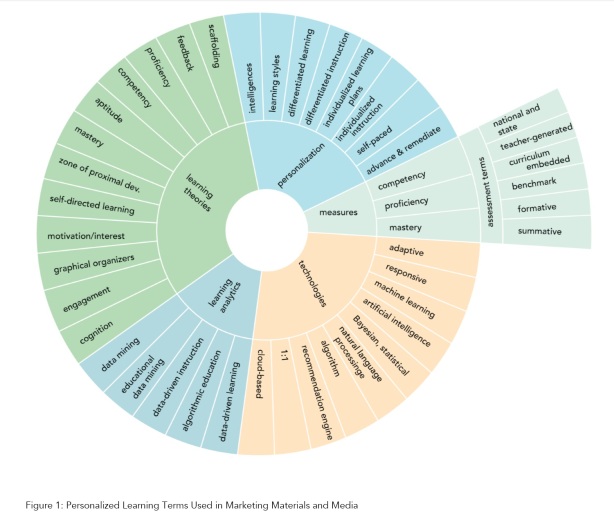

In the latest educational technology plan from the U.S. Department of Education (‘

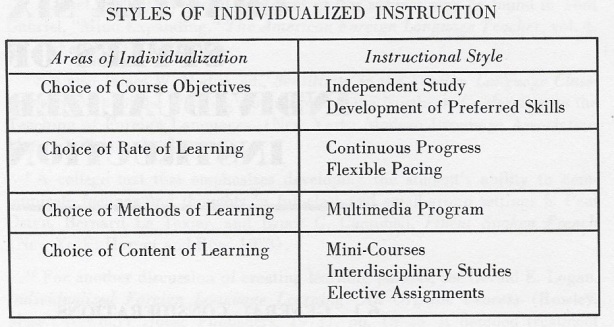

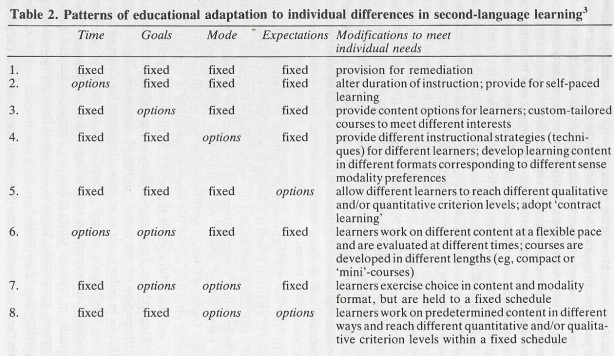

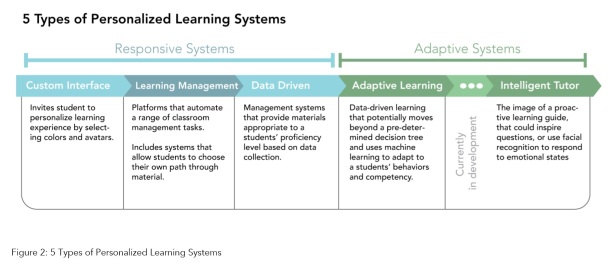

In the latest educational technology plan from the U.S. Department of Education (‘ The main point of adaptive learning tools is to facilitate differentiated instruction. They are, as

The main point of adaptive learning tools is to facilitate differentiated instruction. They are, as

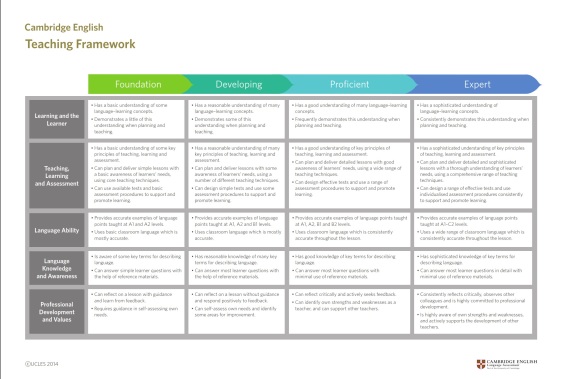

Classroom practice could also form part of such an adaptive system. One tool that could be deployed would be

Classroom practice could also form part of such an adaptive system. One tool that could be deployed would be