From time to time, I have mentioned Programmed Learning (or Programmed Instruction) in this blog (here and here, for example). It felt like time to go into a little more detail about what Programmed Instruction was (and is) and why I think it’s important to know about it.

A brief description

The basic idea behind Programmed Instruction was that subject matter could be broken down into very small parts, which could be organised into an optimal path for presentation to students. Students worked, at their own speed, through a series of micro-tasks, building their mastery of each nugget of learning that was presented, not progressing from one to the next until they had demonstrated they could respond accurately to the previous task.

There were two main types of Programmed Instruction: linear programming and branching programming. In the former, every student would follow the same path, the same sequence of frames. This could be used in classrooms for whole-class instruction and I tracked down a book (illustrated below) called ‘Programmed English Course Student’s Book 1’ (Hill, 1966), which was an attempt to transfer the ideas behind Programmed Instruction to a zero-tech, class environment. This is very similar in approach to the material I had to use when working at an Inlingua school in the 1980s.

An example of how self-paced programming worked is illustrated here, with a section on comparatives.

With branching programming, ‘extra frames (or branches) are provided for students who do not get the correct answer’ (Kay et al., 1968: 19). This was only suitable for self-study, but it was clearly preferable, as it allowed for self-pacing and some personalization. The material could be presented in books (which meant that students had to flick back and forth in their books) or with special ‘teaching machines’, but the latter were preferred.

In the words of an early enthusiast, Programmed Instruction was essentially ‘a device to control a student’s behaviour and help him to learn without the supervision of a teacher’ (Kay et al.,1968: 58). The approach was inspired by the work of Skinner and it was first used as part of a university course in behavioural psychology taught by Skinner at Harvard University in 1957. It moved into secondary schools for teaching mathematics in 1959 (Saettler, 2004: 297).

Enthusiasm and uptake

The parallels between current enthusiasm for the power of digital technology to transform education and the excitement about Programmed Instruction and teaching machines in the 1960s are very striking (McDonald et al., 2005: 90). In 1967, it was reported that ‘we are today on the verge of what promises to be a revolution in education’ (Goodman, 1967: 3) and that ‘tremors of excitement ran through professional journals and conferences and department meetings from coast to coast’ (Kennedy, 1967: 871). The following year, another commentator referred to the way that the field of education had been stirred ‘with an almost Messianic promise of a breakthrough’ (Ornstein, 1968: 401). Programmed instruction was also seen as an exciting business opportunity: ‘an entire industry is just coming into being and significant sales and profits should not be too long in coming’, wrote one hopeful financial analyst as early as 1961 (Kozlowski, 1967: 47).

The new technology seemed to offer a solution to the ‘problems of education’. Media reports in 1963 in Germany, for example, discussed a shortage of teachers, large classes and inadequate learning progress … ‘an ‘urgent pedagogical emergency’ that traditional teaching methods could not resolve’ (Hof, 2018). Individualised learning, through Programmed Instruction, would equalise educational opportunity and if you weren’t part of it, you would be left behind. In the US, two billion dollars were spent on educational technology by the government in the decade following the passing of the National Defense Education Act, and this was added to by grants from private foundations. As a result, ‘the production of teaching machines began to flourish, accompanied by the marketing of numerous ‘teaching units’ stamped into punch cards as well as less expensive didactic programme books and index cards. The market grew dramatically in a short time’ (Hof, 2018).

In the field of language learning, however, enthusiasm was more muted. In the year in which he completed his doctoral studies[1], the eminent linguist, Bernard Spolsky noted that ‘little use is actually being made of the new technique’ (Spolsky, 1966). A year later, a survey of over 600 foreign language teachers at US colleges and universities reported that only about 10% of them had programmed materials in their departments (Valdman, 1968: 1). In most of these cases, the materials ‘were being tried out on an experimental basis under the direction of their developers’. And two years after that, it was reported that ‘programming has not yet been used to any very great extent in language teaching, so there is no substantial body of experience from which to draw detailed, water-tight conclusions’ (Howatt, 1969: 164).

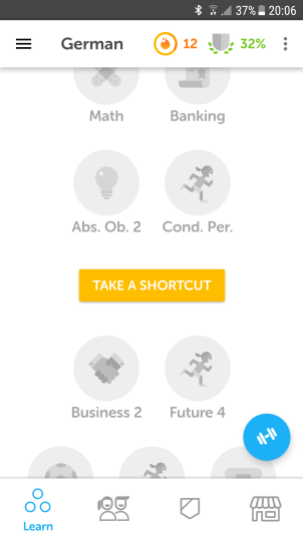

By the early 1970s, Programmed Instruction was already beginning to seem like yesterday’s technology, even though the principles behind it are still very much alive today (Thornbury (2017) refers to Duolingo as ‘Programmed Instruction’). It would be nice to think that language teachers of the day were more sceptical than, for example, their counterparts teaching mathematics. It would be nice to think that, like Spolsky, they had taken on board Chomsky’s (1959) demolition of Skinner. But the widespread popularity of Audiolingual methods suggests otherwise. Audiolingualism, based essentially on the same Skinnerian principles as Programmed Instruction, needed less outlay on technology. The machines (a slide projector and a record or tape player) were cheaper than the teaching machines, could be used for other purposes and did not become obsolete so quickly. The method also lent itself more readily to established school systems (i.e. whole-class teaching) and the skills sets of teachers of the day. Significantly, too, there was relatively little investment in Programmed Instruction for language teaching (compared to, say, mathematics), since this was a smallish and more localized market. There was no global market for English language learning as there is today.

Lessons to be learned

1 Shaping attitudes

It was not hard to persuade some educational authorities of the value of Programmed Instruction. As discussed above, it offered a solution to the problem of ‘the chronic shortage of adequately trained and competent teachers at all levels in our schools, colleges and universities’, wrote Goodman (1967: 3), who added, there is growing realisation of the need to give special individual attention to handicapped children and to those apparently or actually retarded’. The new teaching machines ‘could simulate the human teacher and carry out at least some of his functions quite efficiently’ (Goodman, 1967: 4). This wasn’t quite the same thing as saying that the machines could replace teachers, although some might have hoped for this. The official line was more often that the machines could ‘be used as devices, actively co-operating with the human teacher as adaptive systems and not just merely as aids’ (Goodman, 1967: 37). But this more nuanced message did not always get through, and ‘the Press soon stated that robots would replace teachers and conjured up pictures of classrooms of students with little iron men in front of them’ (Kay et al., 1968: 161).

For teachers, though, it was one thing to be told that the machines would free their time to perform more meaningful tasks, but harder to believe when this was accompanied by a ‘rhetoric of the instructional inadequacies of the teacher’ (McDonald, et al., 2005: 88). Many teachers felt threatened. They ‘reacted against the ‘unfeeling machine’ as a poor substitute for the warm, responsive environment provided by a real, live teacher. Others have seemed to take it more personally, viewing the advent of programmed instruction as the end of their professional career as teachers. To these, even the mention of programmed instruction produces a momentary look of panic followed by the appearance of determination to stave off the ominous onslaught somehow’ (Tucker, 1972: 63).

Some of those who were pushing for Programmed Instruction had a bigger agenda, with their sights set firmly on broader school reform made possible through technology (Hof, 2018). Individualised learning and Programmed Instruction were not just ends in themselves: they were ways of facilitating bigger changes. The trouble was that teachers were necessary for Programmed Instruction to work. On the practical level, it became apparent that a blend of teaching machines and classroom teaching was more effective than the machines alone (Saettler, 2004: 299). But the teachers’ attitudes were crucial: a research study involving over 6000 students of Spanish showed that ‘the more enthusiastic the teacher was about programmed instruction, the better the work the students did, even though they worked independently’ (Saettler, 2004: 299). In other researched cases, too, ‘teacher attitudes proved to be a critical factor in the success of programmed instruction’ (Saettler, 2004: 301).

2 Returns on investment

Pricing a hyped edtech product is a delicate matter. Vendors need to see a relatively quick return on their investment, before a newer technology knocks them out of the market. Developments in computing were fast in the late 1960s, and the first commercially successful personal computer, the Altair 8800, appeared in 1974. But too high a price carried obvious risks. In 1967, the cheapest teaching machine in the UK, the Tutorpack (from Packham Research Ltd), cost £7 12s (equivalent to about £126 today), but machines like these were disparagingly referred to as ‘page-turners’ (Higgins, 1983: 4). A higher-end linear programming machine cost twice this amount. Branching programme machines cost a lot more. The Mark II AutoTutor (from USI Great Britain Limited), for example, cost £31 per month (equivalent to £558), with eight reels of programmes thrown in (Goodman, 1967: 26). A lower-end branching machine, the Grundytutor, could be bought for £ 230 (worth about £4140 today).

This was serious money, and any institution splashing out on teaching machines needed to be confident that they would be well used for a long period of time (Nordberg, 1965). The programmes (the software) were specific to individual machines and the content could not be updated easily. At the same time, other technological developments (cine projectors, tape recorders, record players) were arriving in classrooms, and schools found themselves having to pay for technical assistance and maintenance. The average teacher was ‘unable to avail himself fully of existing aids because, to put it bluntly, he is expected to teach for too many hours a day and simply has not the time, with all the administrative chores he is expected to perform, either to maintain equipment, to experiment with it, let alone keeping up with developments in his own and wider fields. The advent of teaching machines which can free the teacher to fulfil his role as an educator will intensify and not diminish the problem’ (Goodman, 1967: 44). Teaching machines, in short, were ‘oversold and underused’ (Cuban, 2001).

3 Research and theory

Looking back twenty years later, B. F. Skinner conceded that ‘the machines were crude, [and] the programs were untested’ (Skinner, 1986: 105). The documentary record suggests that the second part of this statement is not entirely true. Herrick (1966: 695) reported that ‘an overwhelming amount of research time has been invested in attempts to determine the relative merits of programmed instruction when compared to ‘traditional’ or ‘conventional’ methods of instruction. The results have been almost equally overwhelming in showing no significant differences’. In 1968, Kay et al (1968: 96) noted that ‘there has been a definite effort to examine programmed instruction’. A later meta-analysis of research in secondary education (Kulik et al.: 1982) confirmed that ‘Programmed Instruction did not typically raise student achievement […] nor did it make students feel more positively about the subjects they were studying’.

It was not, therefore, the case that research was not being done. It was that many people were preferring not to look at it. The same holds true for theoretical critiques. In relation to language learning, Spolsky (1966) referred to Chomsky’s (1959) rebuttal of Skinner’s arguments, adding that ‘there should be no need to rehearse these inadequacies, but as some psychologists and even applied linguists appear to ignore their existence it might be as well to remind readers of a few’. Programmed Instruction might have had a limited role to play in language learning, but vendors’ claims went further than that and some people believed them: ‘Rather than addressing themselves to limited and carefully specified FL tasks – for example the teaching of spelling, the teaching of grammatical concepts, training in pronunciation, the acquisition of limited proficiency within a restricted number of vocabulary items and grammatical features – most programmers aimed at self-sufficient courses designed to lead to near-native speaking proficiency’ (Valdman, 1968: 2).

4 Content

When learning is conceptualised as purely the acquisition of knowledge, technological optimists tend to believe that machines can convey it more effectively and more efficiently than teachers (Hof, 2018). The corollary of this is the belief that, if you get the materials right (plus the order in which they are presented and appropriate feedback), you can ‘to a great extent control and engineer the quality and quantity of learning’ (Post, 1972: 14). Learning, in other words, becomes an engineering problem, and technology is its solution.

One of the problems was that technology vendors were, first and foremost, technology specialists. Content was almost an afterthought. Materials writers needed to be familiar with the technology and, if not, they were unlikely to be employed. Writers needed to believe in the potential of the technology, so those familiar with current theory and research would clearly not fit in. The result was unsurprising. Kennedy (1967: 872) reported that ‘there are hundreds of programs now available. Many more will be published in the next few years. Watch for them. Examine them critically. They are not all of high quality’. He was being polite.

5 Motivation

As is usually the case with new technologies, there was a positive novelty effect with Programmed Instruction. And, as is always the case, the novelty effect wears off: ‘students quickly tired of, and eventually came to dislike, programmed instruction’ (McDonald et al.: 89). It could not really have been otherwise: ‘human learning and intrinsic motivation are optimized when persons experience a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in their activity. Self-determination theorists have also studied factors that tend to occlude healthy functioning and motivation, including, among others, controlling environments, rewards contingent on task performance, the lack of secure connection and care by teachers, and situations that do not promote curiosity and challenge’ (McDonald et al.: 93). The demotivating experience of using these machines was particularly acute with younger and ‘less able’ students, as was noted at the time (Valdman, 1968: 9).

The unlearned lessons

I hope that you’ll now understand why I think the history of Programmed Instruction is so relevant to us today. In the words of my favourite Yogi-ism, it’s like deja vu all over again. I have quoted repeatedly from the article by McDonald et al (2005) and I would highly recommend it – available here. Hopefully, too, Audrey Watters’ forthcoming book, ‘Teaching Machines’, will appear before too long, and she will, no doubt, have much more of interest to say on this topic.

References

Chomsky N. 1959. ‘Review of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior’. Language, 35:26–58.

Cuban, L. 2001. Oversold & Underused: Computers in the Classroom. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

Goodman, R. 1967. Programmed Learning and Teaching Machines 3rd edition. (London: English Universities Press)

Herrick, M. 1966. ‘Programmed Instruction: A critical appraisal’ The American Biology Teacher, 28 (9), 695 -698

Higgins, J. 1983. ‘Can computers teach?’ CALICO Journal, 1 (2)

Hill, L. A. 1966. Programmed English Course Student’s Book 1. (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Hof, B. 2018. ‘From Harvard via Moscow to West Berlin: educational technology, programmed instruction and the commercialisation of learning after 1957’ History of Education, 47:4, 445-465

Howatt, A. P. R. 1969. Programmed Learning and the Language Teacher. (London: Longmans)

Kay, H., Dodd, B. & Sime, M. 1968. Teaching Machines and Programmed Instruction. (Harmondsworth: Penguin)

Kennedy, R.H. 1967. ‘Before using Programmed Instruction’ The English Journal, 56 (6), 871 – 873

Kozlowski, T. 1961. ‘Programmed Teaching’ Financial Analysts Journal, 17 / 6, 47 – 54

Kulik, C.-L., Schwalb, B. & Kulik, J. 1982. ‘Programmed Instruction in Secondary Education: A Meta-analysis of Evaluation Findings’ Journal of Educational Research, 75: 133 – 138

McDonald, J. K., Yanchar, S. C. & Osguthorpe, R.T. 2005. ‘Learning from Programmed Instruction: Examining Implications for Modern Instructional Technology’ Educational Technology Research and Development, 53 / 2, 84 – 98

Nordberg, R. B. 1965. Teaching machines-six dangers and one advantage. In J. S. Roucek (Ed.), Programmed teaching: A symposium on automation in education (pp. 1–8). (New York: Philosophical Library)

Ornstein, J. 1968. ‘Programmed Instruction and Educational Technology in the Language Field: Boon or Failure?’ The Modern Language Journal, 52 / 7, 401 – 410

Post, D. 1972. ‘Up the programmer: How to stop PI from boring learners and strangling results’. Educational Technology, 12(8), 14–1

Saettler, P. 2004. The Evolution of American Educational Technology. (Greenwich, Conn.: Information Age Publishing)

Skinner, B. F. 1986. ‘Programmed Instruction Revisited’ The Phi Delta Kappan, 68 (2), 103 – 110

Spolsky, B. 1966. ‘A psycholinguistic critique of programmed foreign language instruction’ International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, Volume 4, Issue 1-4: 119–130

Thornbury, S. 2017. Scott Thornbury’s 30 Language Teaching Methods. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Tucker, C. 1972. ‘Programmed Dictation: An Example of the P.I. Process in the Classroom’. TESOL Quarterly, 6(1), 61-70

Valdman, A. 1968. ‘Programmed Instruction versus Guided Learning in Foreign Language Acquisition’ Die Unterrichtspraxis / Teaching German, 1 (2), 1 – 14

[1] Spolsky’ doctoral thesis for the University of Montreal was entitled ‘The psycholinguistic basis of programmed foreign language instruction’.

In

In

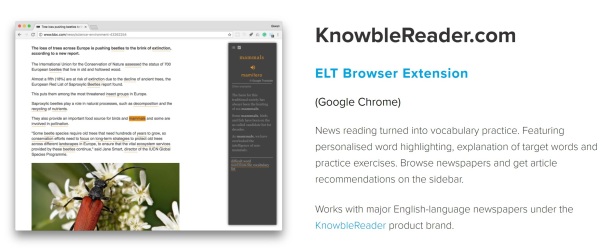

One of the reasons that Google Translate has improved is that it no longer treats individual words as individual lexical items. It analyses groups of words and translates chunks or phrases (see, for example, the way it translates ‘as part of’). It doesn’t do word-for-word translation. Knowble, however, have set their software to ask Google for translations of each word as individual items, so the phrase ‘as part of’ is translated ‘comme’ + ‘partie’ + ‘de’. Whilst this example is comprehensible, problems arise very quickly. ‘Cotton buds’ (‘cotons-tiges’) become ‘coton’ + ‘bourgeon’ (= botanical shoots of cotton). Phrases like ‘in time’, ‘run into’, ‘sleep it off’ ‘take its course’, ‘fire station’ or ‘going on’ (all from the stoned raccoon text) all cause problems. In addition, Knowble are not using any parsing tools, so the system does not identify parts of speech, and further translation errors inevitably appear. In the short article of 240 words, about 10% are wrongly translated. Knowble claim to be using NLP tools, but there’s no sign of it here. They’re just using Google Translate rather badly.

One of the reasons that Google Translate has improved is that it no longer treats individual words as individual lexical items. It analyses groups of words and translates chunks or phrases (see, for example, the way it translates ‘as part of’). It doesn’t do word-for-word translation. Knowble, however, have set their software to ask Google for translations of each word as individual items, so the phrase ‘as part of’ is translated ‘comme’ + ‘partie’ + ‘de’. Whilst this example is comprehensible, problems arise very quickly. ‘Cotton buds’ (‘cotons-tiges’) become ‘coton’ + ‘bourgeon’ (= botanical shoots of cotton). Phrases like ‘in time’, ‘run into’, ‘sleep it off’ ‘take its course’, ‘fire station’ or ‘going on’ (all from the stoned raccoon text) all cause problems. In addition, Knowble are not using any parsing tools, so the system does not identify parts of speech, and further translation errors inevitably appear. In the short article of 240 words, about 10% are wrongly translated. Knowble claim to be using NLP tools, but there’s no sign of it here. They’re just using Google Translate rather badly. NLP tools of some kind are presumably being used to select the words that get underlined. Exactly how this works is unclear. On the whole, it seems that very high frequency words are ignored and that lower frequency words are underlined. Here, for example, is the list of words that were underlined in the stoned raccoon text. I’ve compared them with (1) the CEFR levels for these words in the English Profile Text Inspector, and (2) the frequency information from the Macmillan dictionary (more stars = more frequent). In the other articles, some extremely high frequency words were underlined (e.g. price, cost, year) while much lower frequency items were not.

NLP tools of some kind are presumably being used to select the words that get underlined. Exactly how this works is unclear. On the whole, it seems that very high frequency words are ignored and that lower frequency words are underlined. Here, for example, is the list of words that were underlined in the stoned raccoon text. I’ve compared them with (1) the CEFR levels for these words in the English Profile Text Inspector, and (2) the frequency information from the Macmillan dictionary (more stars = more frequent). In the other articles, some extremely high frequency words were underlined (e.g. price, cost, year) while much lower frequency items were not. Vocabulary learning

Vocabulary learning The claim that Knowble’s ‘learning effect is proven scientifically’ seems to me to be without any foundation. If there has been any proper research, it’s not signposted anywhere. Sure, reading lots of news articles (with a look-up function – if it works reliably) can only be beneficial for language learners, but they can do that with any decent dictionary running in the background.

The claim that Knowble’s ‘learning effect is proven scientifically’ seems to me to be without any foundation. If there has been any proper research, it’s not signposted anywhere. Sure, reading lots of news articles (with a look-up function – if it works reliably) can only be beneficial for language learners, but they can do that with any decent dictionary running in the background.

An interest in self-paced learning can be traced back to the growth of mass schooling and age-graded classes in the 19th century. In fact, the ‘factory model’ of education has never existed without critics who saw the inherent problems of imposing uniformity on groups of individuals. These critics were not marginal characters. Charles Eliot (president of Harvard from 1869 – 1909), for example, described uniformity as ‘the curse of American schools’ and argued that ‘the process of instructing students in large groups is a quite sufficient school evil without clinging to its twin evil, an inflexible program of studies’ (Grittner, 1975: 324).

An interest in self-paced learning can be traced back to the growth of mass schooling and age-graded classes in the 19th century. In fact, the ‘factory model’ of education has never existed without critics who saw the inherent problems of imposing uniformity on groups of individuals. These critics were not marginal characters. Charles Eliot (president of Harvard from 1869 – 1909), for example, described uniformity as ‘the curse of American schools’ and argued that ‘the process of instructing students in large groups is a quite sufficient school evil without clinging to its twin evil, an inflexible program of studies’ (Grittner, 1975: 324).

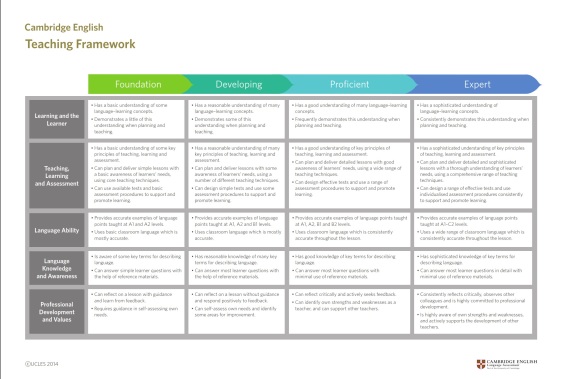

The main point of adaptive learning tools is to facilitate differentiated instruction. They are, as

The main point of adaptive learning tools is to facilitate differentiated instruction. They are, as

Classroom practice could also form part of such an adaptive system. One tool that could be deployed would be

Classroom practice could also form part of such an adaptive system. One tool that could be deployed would be